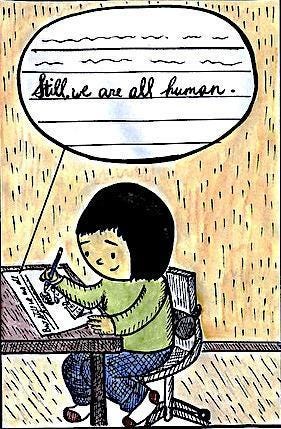

Still We Are All Human

A review of Dawn K. Wing's "Tye Leung Schulze: Translator for Justice" & interview with the creator

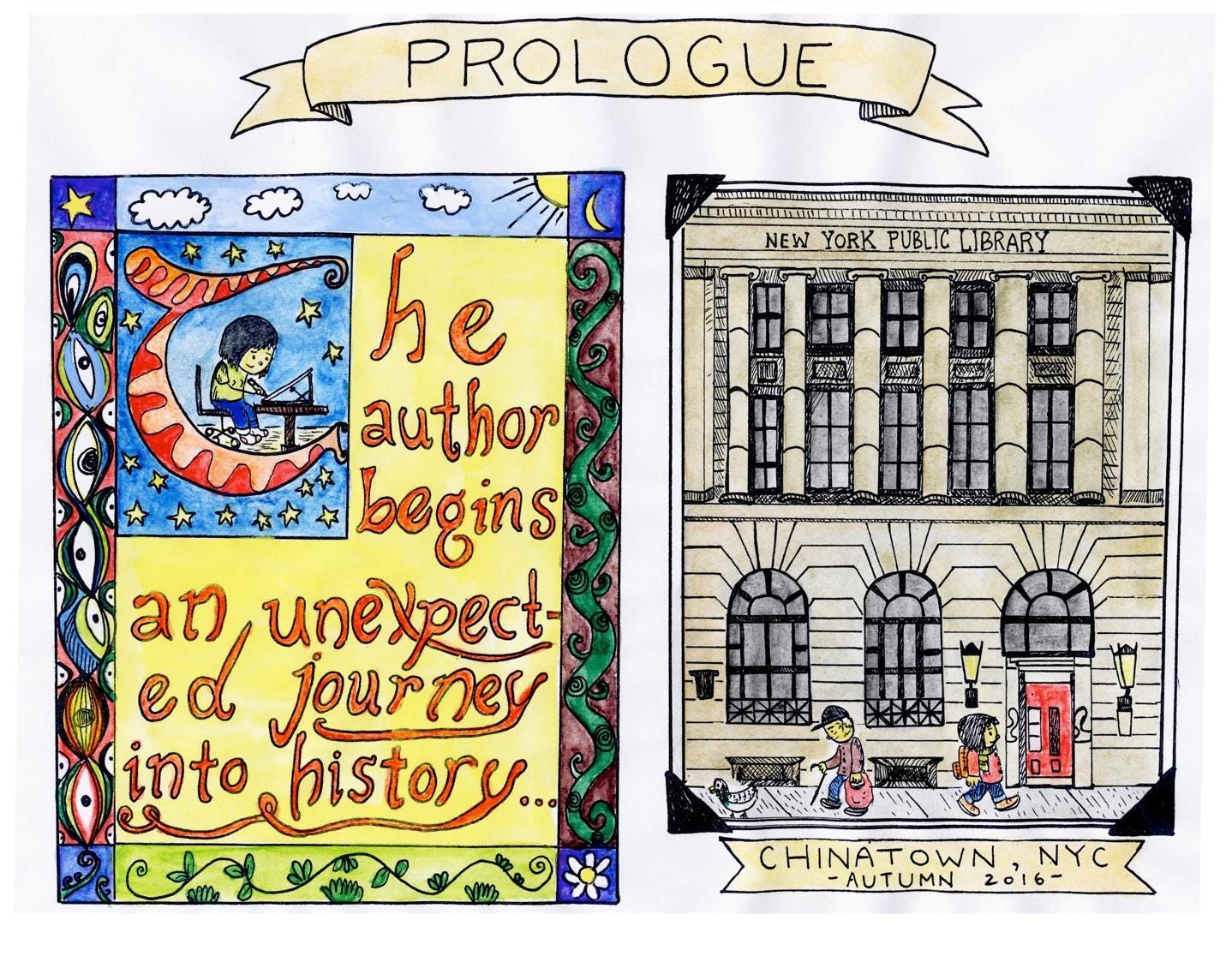

We had the pleasure of meeting Dawn Wing at the Southwest Popular American Culture Conference earlier this year. A librarian and comics creator, Dawn has created her own small press to publish comics, Water Pig Press. Dawn shared her comics biography, Tye Leung Schulze: Translator for Justice, with us and we greatly enjoyed her story of research and connection with the translator cum activist.

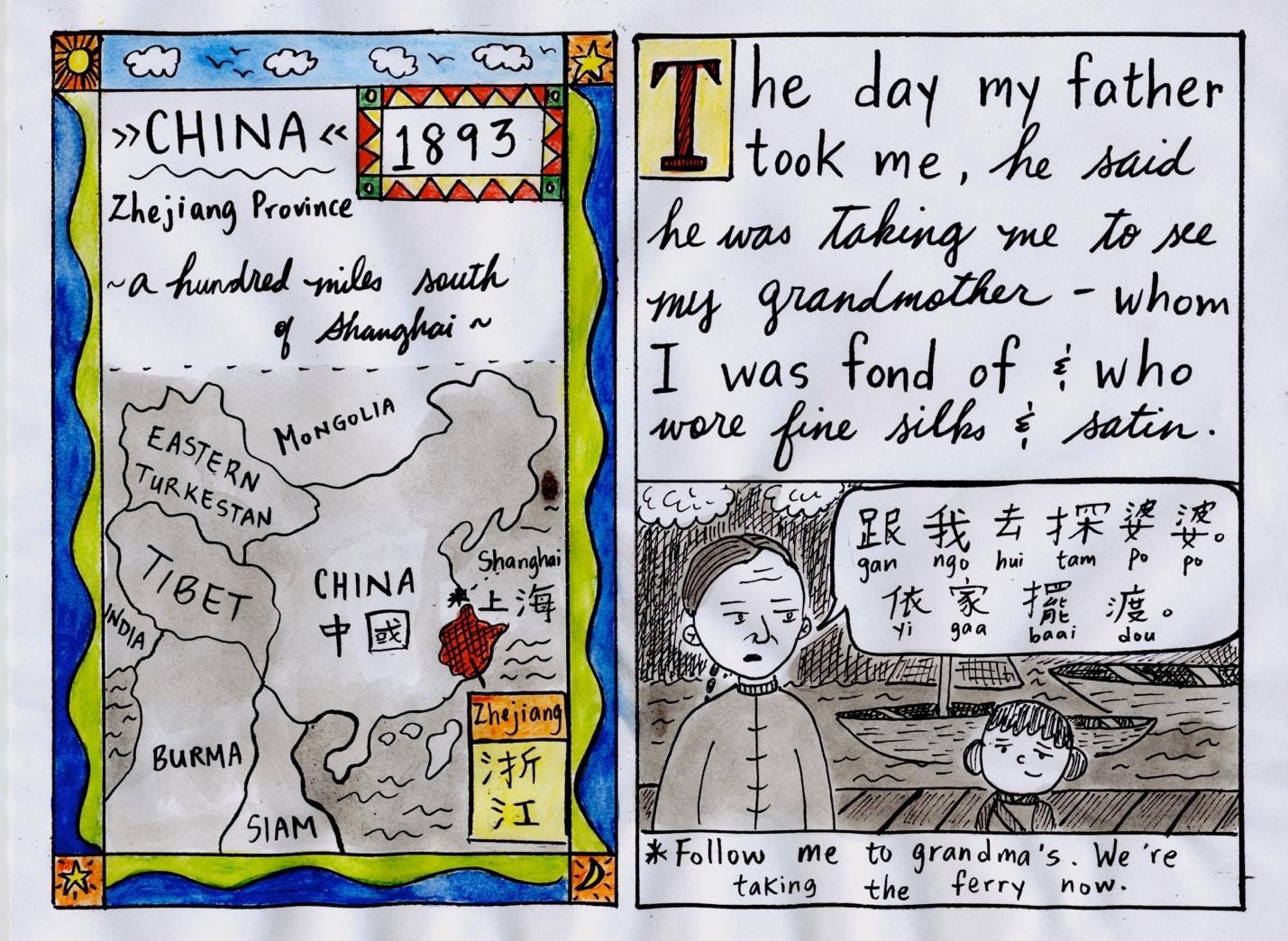

The biography describes the life of Tye Leung Schulze (1887-1972), who was the first Chinese American woman to vote in a presidential election (in 1912), and the first Chinese American civil servant. We hear Tye’s story first through Dawn’s discovery at an exhibit on the legal history of Chinese American women; when Dawn dives into researching more about Tye, we hear more about Tye and her legacy from her grandson and then in her words, from a short memoir she penned. Born shortly after the Chinese Exclusion Act, Tye lived during a time when it was common for a young Chinese woman to live as a “errand girl” in someone else’s house and to be married off in an arranged marriage to an unknown man. Tye was able to move into a Presbyterian mission and learn English; it was here that her work as a translator began, translating for other young Chinese women at doctors’ offices and courts. Translating soon paves a path to activism for Tye, defending the rights of immigrants and women.

Wing uses collage, color, and lettering to energize the sometimes stale genre of biography. Lynda Barry’s influence (particularly the autobiofictionalography One! Hundred! Demons!) is seen in these stylistic choices, which seems fitting as Wing’s book doesn’t reveal Tye’s life in a traditional, linear, manner. Tye’s story is told through a kaleidoscope of sources, which makes for an engaging, messier story of an overlooked life. Photographs, maps, newspaper articles, and other source materials are combined with Wing’s colorful drawings and additions. Wing takes advantage of the visual comic form to show readers speech bubbles with English and Chinese speech/language. The Chinese dialogue is both spelled and written in characters. Her use of various washes of color helps communicate moods and periods of time. All these visual cues help to make the story of Tye’s life more impactful, and memorable.

Wing’s book is both informative and inspirational–while remaining a refreshing read for summer. Below, Wing talks to us about some of her inspirations and her current project.

Describe your comics journey—how did you get into making comics?

Though I read comics as a kid and majored in Studio Arts and Art History as an undergraduate, I fell into creating comics in my early twenties while living and teaching English in Japan, which played a major role in getting me to create what would be my first diary/zine comics. As I was learning Japanese while teaching English to high school students in public schools, I was encouraged by senseis/teachers to read manga like “Sazai-san” to improve my reading, writing and vocabulary skills. I also was reading the works of the “godfather of manga” Tezuka Osamu, which blew my mind in terms of his prolific output of content and aliveness of line-work. I would soon buy my first ink nibs and brushes at Kinokuniya Bookstore, and just draw scenes of my everyday experiences navigating life in Japan as a gai-jin (foreigner) who was trying to grasp the language and customs unfamiliar to me.

I would share some of these comic strips with senseis (using the school’s copy machine—they did not seem to mind), where they became a hit. Also, given that Japan’s manga-reading culture has a long, deep history, I would integrate comics into my English lessons and encourage students to create their own personal comics in classroom handouts. I would also include my own illustrations and captions in worksheets to make English reading and writing activities a little less dry and hopefully more helpful to students as well. At the very least, allowing my inner-comics geek to come out maybe made me more appealing and approachable to students.

Upon returning to the US, I would eventually get into making mostly “auto-bi-fictional” comic zines, and participating at zines and comic festivals. The inspiration and opportunities for creating nonfiction graphic narrative books which I have recently published came about from a series of serendipitous events connected to my journey in learning more about the history of Chinese American women in the United States. I discuss this more in the prologue of my first book “Tye Leung Schulze: Translator for Justice, a comics biography.” In short, when the grandson of Tye Leung Schulze and I were communicating initially about a different research project, he had discovered my “auto-bi-fictional” webcomics. Impressed by my work, he suggested I illustrate his grandmother’s life and legacy as a comic so that her story could be accessible to a wider audience. I was honored by his unexpected proposal, to which, of course, I agreed to take on; and from there, the rest is herstory.

How did you develop your voice/unique comics style?

Since an early age, I have enjoyed creating all kinds of art: painting, printing, photography, collaging, drawing, etc. So, I am particularly appreciative of experimentation with visual storytelling which inspires me to push my own boundaries as a comics artist to take creative risks in ways that allows for freedom of expression and truth.

As a child, I read Garfield, Peanuts, Calvin and Hobbes, and other treasures of the full-color Sunday comics strips published in the NY Daily News. I loved the simple yet rhythmic line work that danced on the page with dialogue and thoughts captured in puffy bubbles—the sophisticated, swift set-up of jokes and punchlines. I loved peering into the internal and imaginary world of the characters, particularly those of Calvin and Hobbes. I can recall creating one-panel comic drawings for my parents with stick figures and word bubbles, and I have no doubt those early scribbles and scratches were inspired by the Sunday comic strips I read.

Years later, when I started creating comic zines, I would intuitively keep to this kind of simple aesthetic of drawing characters, objects and places. The simplicity of form allowed for me to produce and distribute comics efficiently while working full-time, first as a public school teacher and now as an academic librarian. I really love the comics style of Ivan Brunetti and Lynda Barry, with whom I had the honor of studying comics during my graduate school years at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 2011-2013. Studying with Lynda Barry taught me the importance of getting to the heart of the story through writing and sketching first, then allowing the artistic form and details to evolve from there.

Another key influence: I was raised Catholic, and went to church for Sunday Mass every week with my family. (As I write this, it seems apparent to me that Sunday was a pivotal day of the week in influencing me as a young budding artist!). We were parishioners at Transfiguration Church on Mott Street in New York’s historic Chinatown. Though possessing an unassuming façade, the church’s interior drew attention from tourists for a reason: it was packed with the most vivid paintings of saints and Biblical scenes from wall to wall and on the ceiling. I was not able to articulate it then, but I felt the power of telling stories with images and words in a way that moved the spirit and soul.

Years later, I would learn about illuminated manuscripts (which I would consider a form of comics or at least visual storytelling), and fell in love with the incredibly detailed calligraphy, saturated coloring and animated depictions of subjects on each page. When I decided to take on the task of illustrating the lives of two incredible Chinese Christian women Tye Leung Schulze and Tien Fu Wu, I felt compelled to return to my Catholic roots, so to speak (I no longer actively/formally practice the faith), by adapting their stories into a format that is similar to the Illuminated manuscript.

How do you think the comics form creates a community forum?

In addition to being a comics artist, I am also an educator and librarian who enthusiastically loves promoting all things comics to anyone (faculty, students, community members, comics festival goers, etc.) who is willing to listen. In my professional experiences, I believe that a sense of community could be fostered through the collective creation of comics in the context of exploring history, identity and memory. In my role as a teacher-librarian, I have had the opportunity to teach comics-making in classrooms, libraries, comics/zines festivals, and academic conferences. When participants come together to experiment with creative self-expression through making comic zines, I structure activities so that they are fun and accessible for people of all ages and backgrounds.

Leading workshops with quick brainstorming exercises using themed-prompts, I encourage participants to trust their inner-creative intuition to choose the tools, words and media (eg: pencil, paper, digital photos, magazines for collaging, etc.)— whatever they are drawn towards to just getting their stories onto the page. If there is time at the end of the workshops/class sessions, participants read aloud their comic zines, and if comfortable, share their thoughts and feelings about the comics-making process. Afterwards, it is my hope they will also share these experiences with their friends, family, peers and communities to spread the joy of making comics anytime, anywhere!

Are you working on something now?

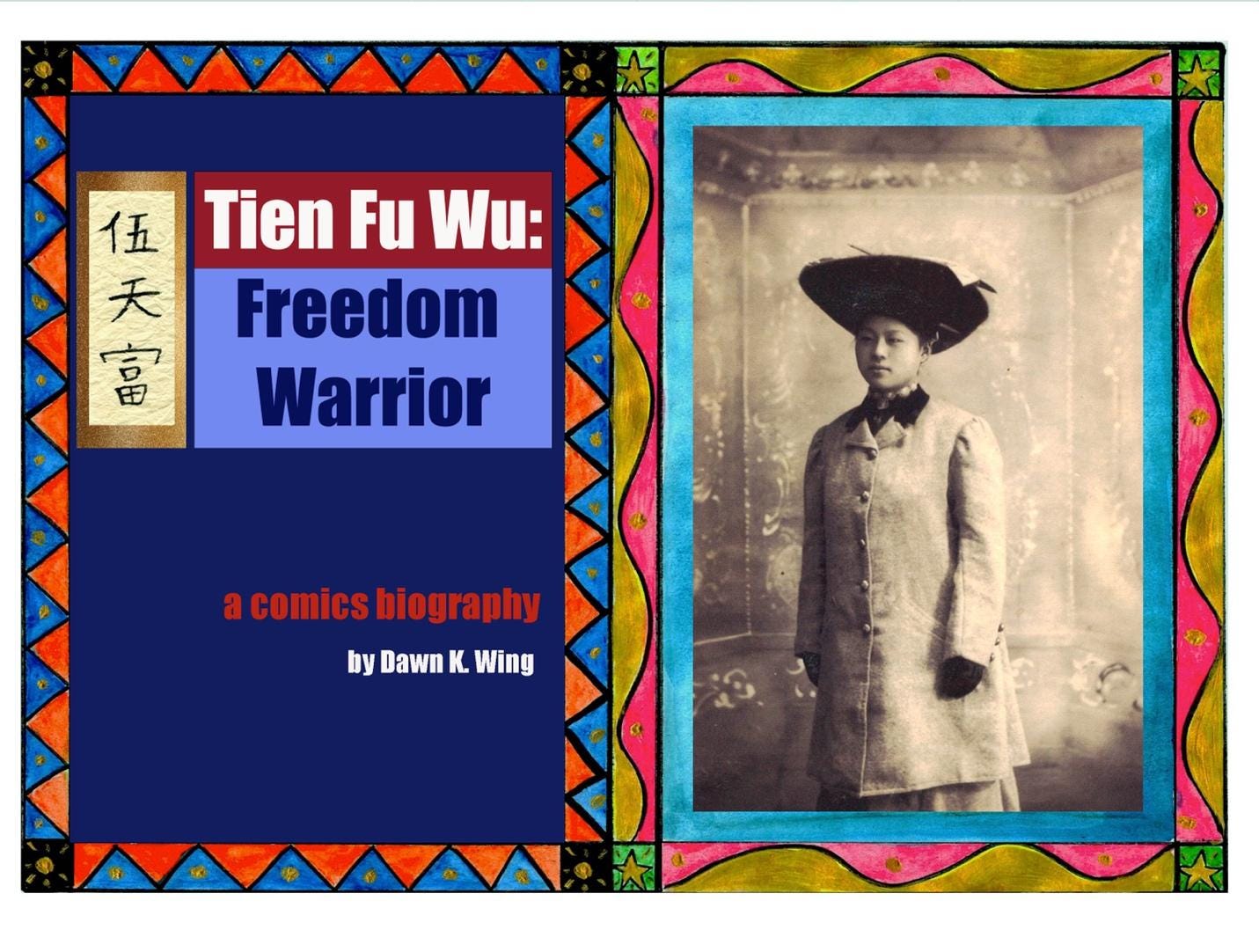

Yes! I just completed my second full-length graphic narrative book, “Tien Fu Wu: Freedom Warrior,” a comics biography about another fierce Chinese American translator for justice who escaped enslavement as a child and dedicated her life to working as an assistant superintendent at the Presbyterian Mission Home for Girls in San Francisco’s Chinatown at the turn of the 20th century. I received the 2022 Minnesota State Art Board’s Creative Support for Individuals grant to complete and distribute copies of this book.

I will be exhibiting and selling copies of this and other works such as “Tye Leung Schulze: Translator for Justice – a comics biography” at the following upcoming comics festivals: Toronto Comic Arts Festival/ TCAF (June 17-19), Autoptic Festival in Minneapolis, MN (August 13-14) and Small Press Expo/SPX in Bethesda, MD (Sept. 17-18).

In addition to exhibiting comics, I will be participating at TCAF’s inaugural academic symposium’s poster session titled, “Promoting diverse voices in comics through campus and community engagement: An academic librarian’s experience” on Friday, June 17th.

To order books and get updates on my creative activities, visit www.waterpigpress.com.

I can be contacted via email at waterpigpress@gmail.com

Follow me on Instagram: @ComixDawn.

Dawn Wing (she/her) is a third-generation Chinese American who was born and raised in Queens, NY. Her Chinese zodiac animal is the water pig.

After earning a Bachelor’s degree in Studio Art and Art History at Wellesley College, Dawn went to teach English in Japan where she rediscovered her love for reading and creating comics. Upon returning to the U.S., she taught English as a Second Language using comics in the classroom with high school students, and eventually decided to become a librarian. Throughout this time, Dawn kept drawing, writing, and producing zines as creative outlets for self-expression. She debuted her first comics biography book, “Tye Leung Schulze: Translator for Justice” (Water Pig Press) in 2021. Her next nonfiction graphic narrative book, “Tien Fu Wu: Freedom for Justice” will be released during summer 2022.

Currently based in the Twin Cities, Minnesota, Dawn enjoys all things art, bicycling, swimming, traveling, gardening and hanging out with her two hamsters, Rumi and Momo. Find out what she’s up to at www.waterpigpress.com.

What delightful interview and introduction to her work!