Universal truths are growing in poetic lines, panels of powerful imagery, and narratives of others’ lives. This fall we’re digging into stacks of graphic memoir–Amaris is teaching graphic memoir at the University of New Mexico, and Nora is integrating comics into a pivotal program for Domestic Abuse Awareness Month in October, spotlighting comics’ therapeutic potential. We’ve been chatting about the power of a true story well told, and in particular, the glimpses and reflection gained from graphic memoir. We both like a graphic memoir that’s less linear, distilled around a fraction of a life–an impactful event, an obsession, a daunting question–so we thought we’d dig in, in these first weeks of classes, to say a few words about why we love to read graphic memoirs.

From eavesdropping to people-watching to reading “oversharing” captions on Instagram, we're always hungry to know how other people live and what they experience. Graphic memoirs provide a sense of intimacy as they let us glimpse into another’s life, showing us real details in the panels. Eyewitness accounts can transport us into a historical moment, rounding out a newspaper headline with the insight of someone who experienced it. Through well drawn stories, we can attempt to understand the complexity of other cultures, near and far. We empathize with first-person stories, and relate to experiences that parallel our own stories, sometimes learning how to think about something in our own lives differently. In comix, it is common to tackle taboo subjects, such as shame, substance abuse, terminal illness, grief, and domestic abuse. Some are brutally honest–or even exhibitionist in their transgressions–to rail against oppressive cultures. Breaking these boundaries can empower the reader; telling these stories through images, in particular, can inspire.

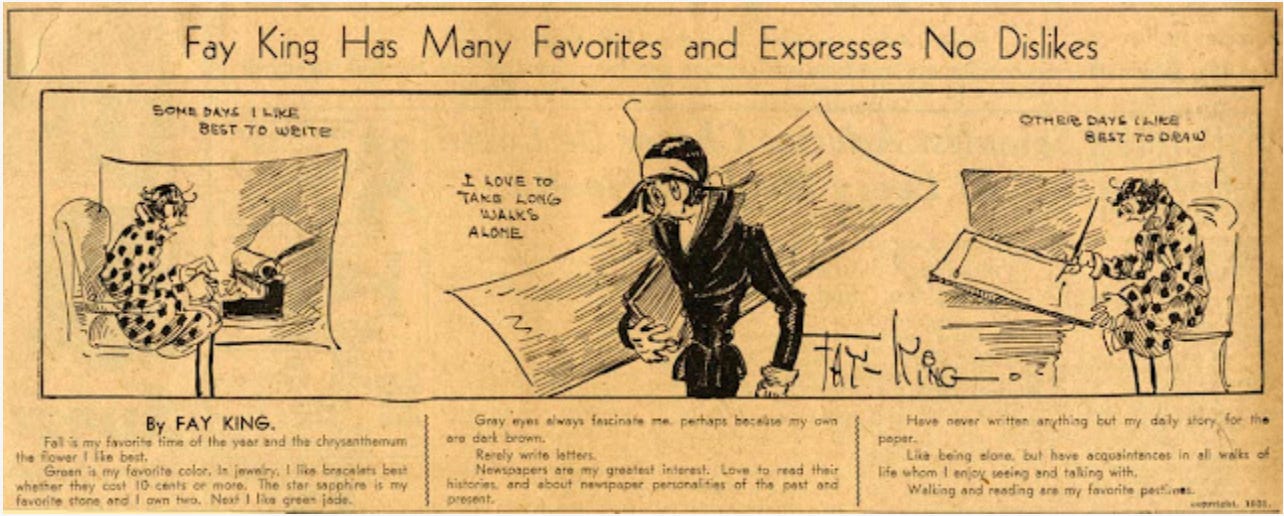

Naturally, what sets comic memoirs apart is their use of imagery. But how does this blend of image and text reshape the memoir format? To understand this, we can trace back to the early beginnings of this hybrid form. We see some emergence of the intersection of real life and comics in some newspaper comic strips of the early 20th century. For example, in her strips from the 1910s and ‘20s Fay King often included her comic avatar, who communicated her observations and insights, her whims and likes, and her quirks and musings.

We see the writer and artist embodied, the shape of her clothes, the expression captured in her eyes, how she sits at her typewriter. In comics, seeing the stylistic choices from each unique creator adds another layer of “knowing” them: it is another aspect to interpret, unlike traditional memoir.

But, even though this inclusion of a comic self lets the reader inhabit a creator’s world more fully, the explicit use of the creator’s own life was rare in the period that comics were most popular (1930s-1950s). Comics were a place for made-up stories and superheroes, or editorialized perspectives on current events. That is, until the underground comics of the 1960s and 70s, when the freedom of no guidelines from publishers or the government allowed for deeper and more complex and honest explorations of the self.

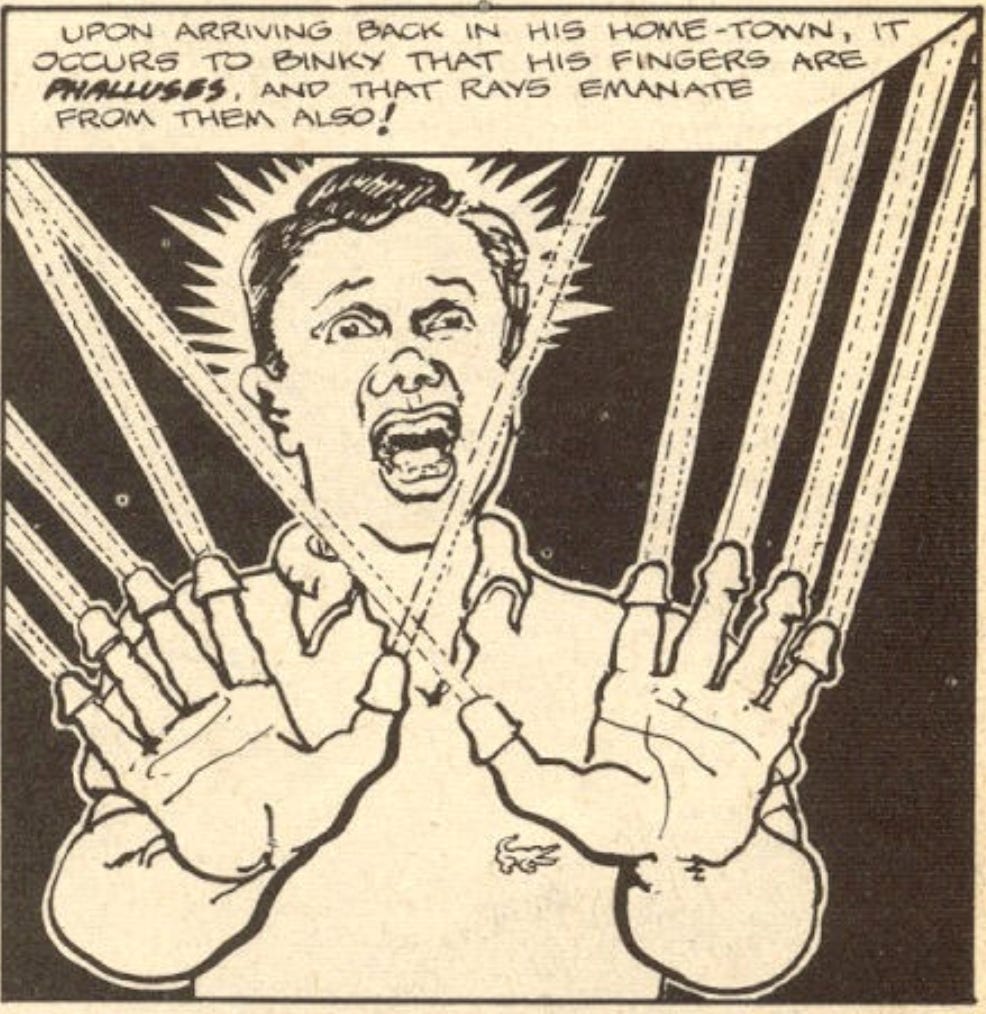

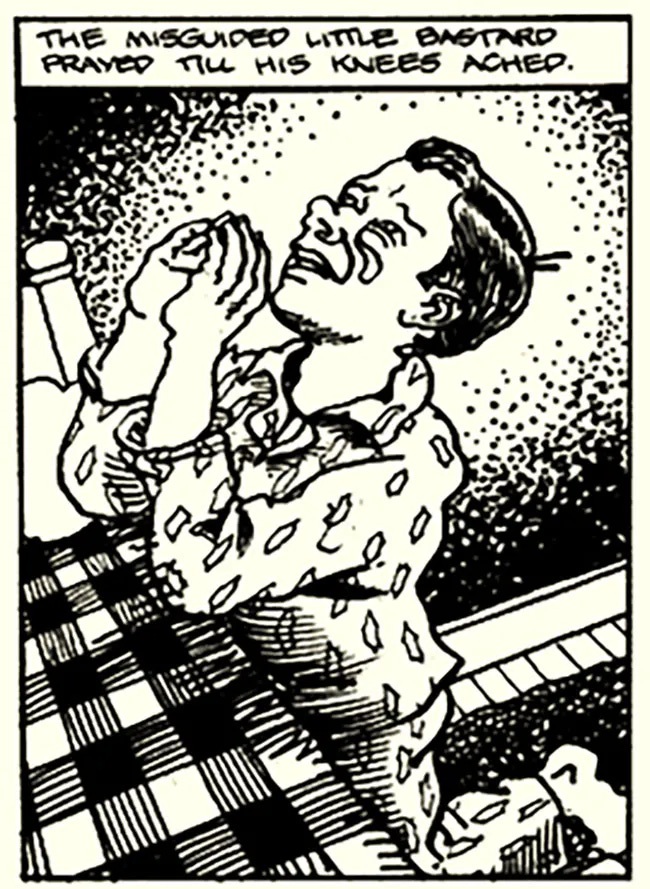

Justin Green is credited with starting the autobiographical comics genre in 1972 with his serialized look at his own life in Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary. In his groundbreaking work, Green used image to quickly and powerfully convey the clash between the Roman Catholicism he grew up with and his coming of age. It’s hard to imagine how words alone could show the sex-related guilt the main character feels as he visualizes his fingers as phalluses.

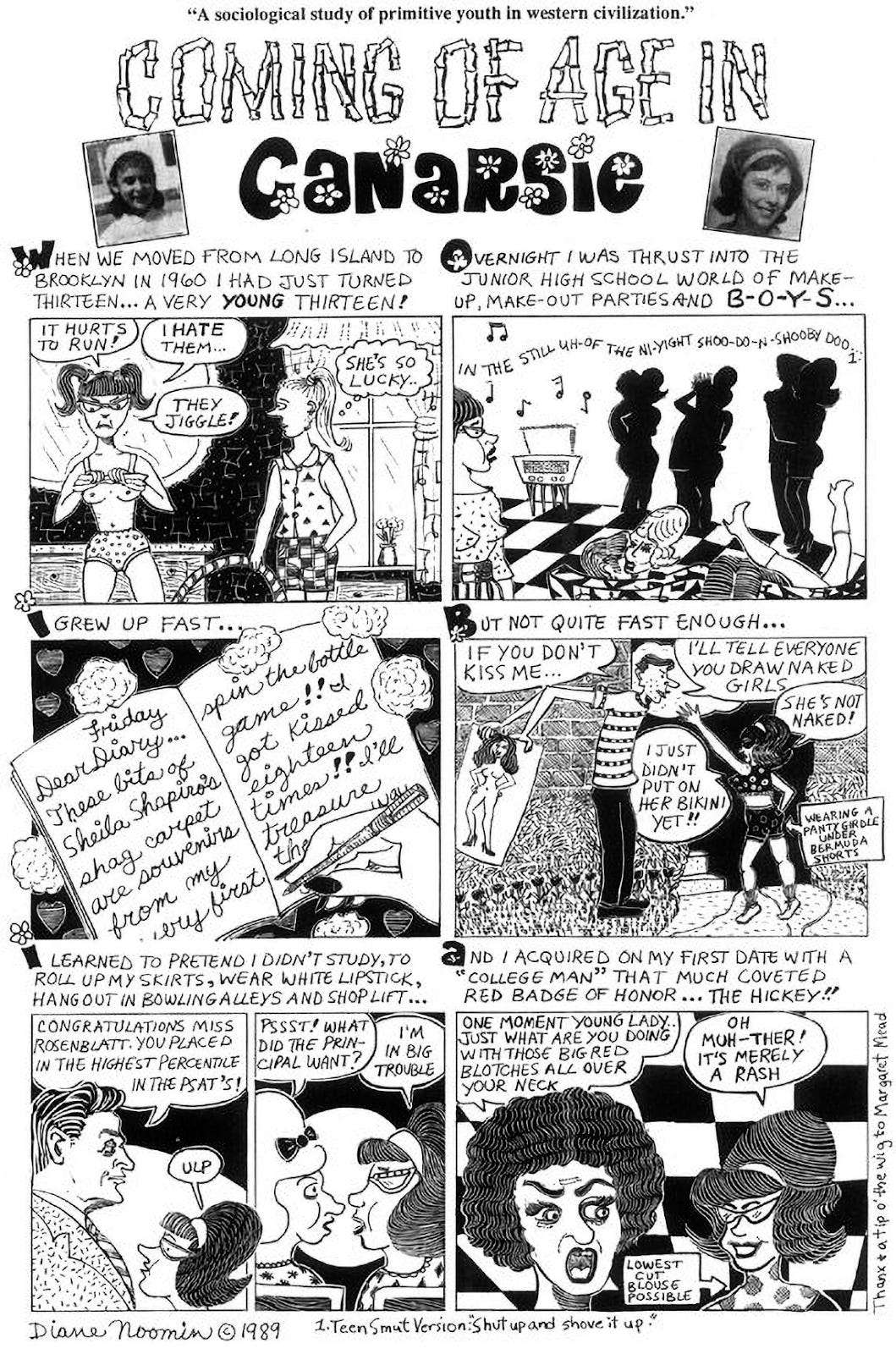

Other underground comic creators tackled autobio, like many of the female artists whose work appeared in Wimmen’s Comix. Diane Noomin, Aline Kominksy-Crumb, Dawn Wings, Mary Fleener, and others drew memoir comics, or at least memoir-adjacent. The “real-life” comics of underground comics by women were feminist and radical because they showed what a women’s real life was–their concerns from the mundane to the major, their fantasies and failures. This ability to be honest in content and art (with so many distinct styles and capacities) would influence comics to come.

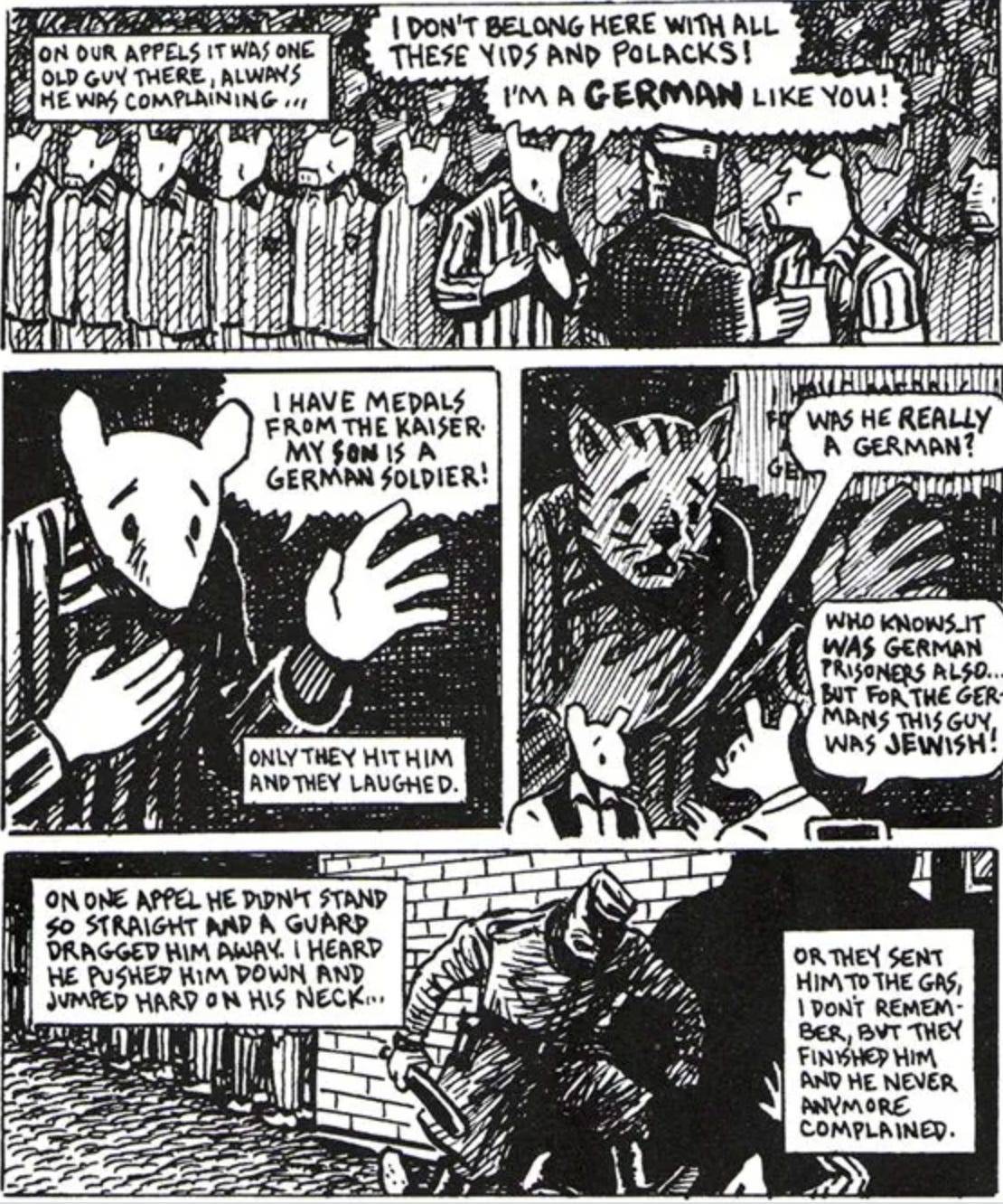

The (arguably) most famous comic memoir, Maus by Art Spiegelman, began in 1980. Here we saw Spiegleman use the comic form to stunning effect. His visual metaphor of people as animals clearly and painfully showed the hierarchy at the time of the Holocaust. Through his drawings, Speigleman conveyed more “truth” than simply his own and his father’s story–bridging the macrohorrors of the Holocaust and their relationship.

Memoir comics like these are popular in our classes and book clubs, because they offer a unique and tangible form of truth, for the reader and the teller. By laying bare their thoughts, aspirations, and setbacks in a visceral, visual format, graphic memoir artists cultivate a connection with readers. Their honesty in both content and distinctive art styles gives readers a sense of representation, ensuring that diverse experiences are seen and recognized.

The beauty of memoir lies in its democratic essence—each individual, given their unique experiences and passions, can potentially craft one. Comics encapsulate everything, from the mundane rhythms of daily life to epochal events, painting a vivid picture of the human experience. Graphic memoir, with its combination of text and image, spans a vast stylistic spectrum—from raw, untrained sketches to polished artistry—and diverse themes, all artfully told. As William Zinsser writes, “Memoir isn’t the summary of a life; it’s a window into a life, very much like a photograph in its selective composition. It may look casual and even random, calling up bygone events. It’s not, it’s a deliberate construction.”

Here’s a comics prompt to get you doodling alongside students this fall semester:

Every image has a story behind it—whether it's a photograph capturing a fleeting moment or a document that has witnessed the passage of time. Look through the photos on your phone (or your personal archives, albums, shoeboxes, etc.) and select a photograph or document that resonates with you. This image will serve as both an artifact and a fact, the cornerstone upon which you'll build your comic.

Freewrite, reflecting on:

Where and when was this image created? How might you draw the background or context of this photograph or document–sketch the setting either in words or drawings.

What emotions does this image evoke in you? Are they feelings of nostalgia, sorrow, joy, shame, or perhaps a complex mix? How might you represent the emotions using symbols, colors, facial expressions, or body language?

Who are the primary figures or elements present in the image? What role do they play in your image, in your life?

Why did you choose this particular image? Does it mark a turning point, a beginning, an end, or a memorable instance in your life? Does this image reflect change or growth in your life? An obsession or a question? A passion?

Draw:

Turn your paper in landscape orientation. Sketch your image in the center of the paper. How might you draw the "before" and "after" of the moment captured in the image?