Making Nonfiction Comics

We ask sticky questions about power relationships with the real life people who may feature in your comic and go through safety precautions if you’re going to a protest.

Autobiographix loves a comic-making companion—we’ve used guides from Scott McCloud, Lynda Barry, Kelcey Ervick, and more in the classroom and in our own practice. So, when we learned that comic creators, stewards, editors, and aficionados Eleri Harris and Shay Mirk were coming out with their own guide, Making Nonfiction Comics, we couldn't wait to dive in.

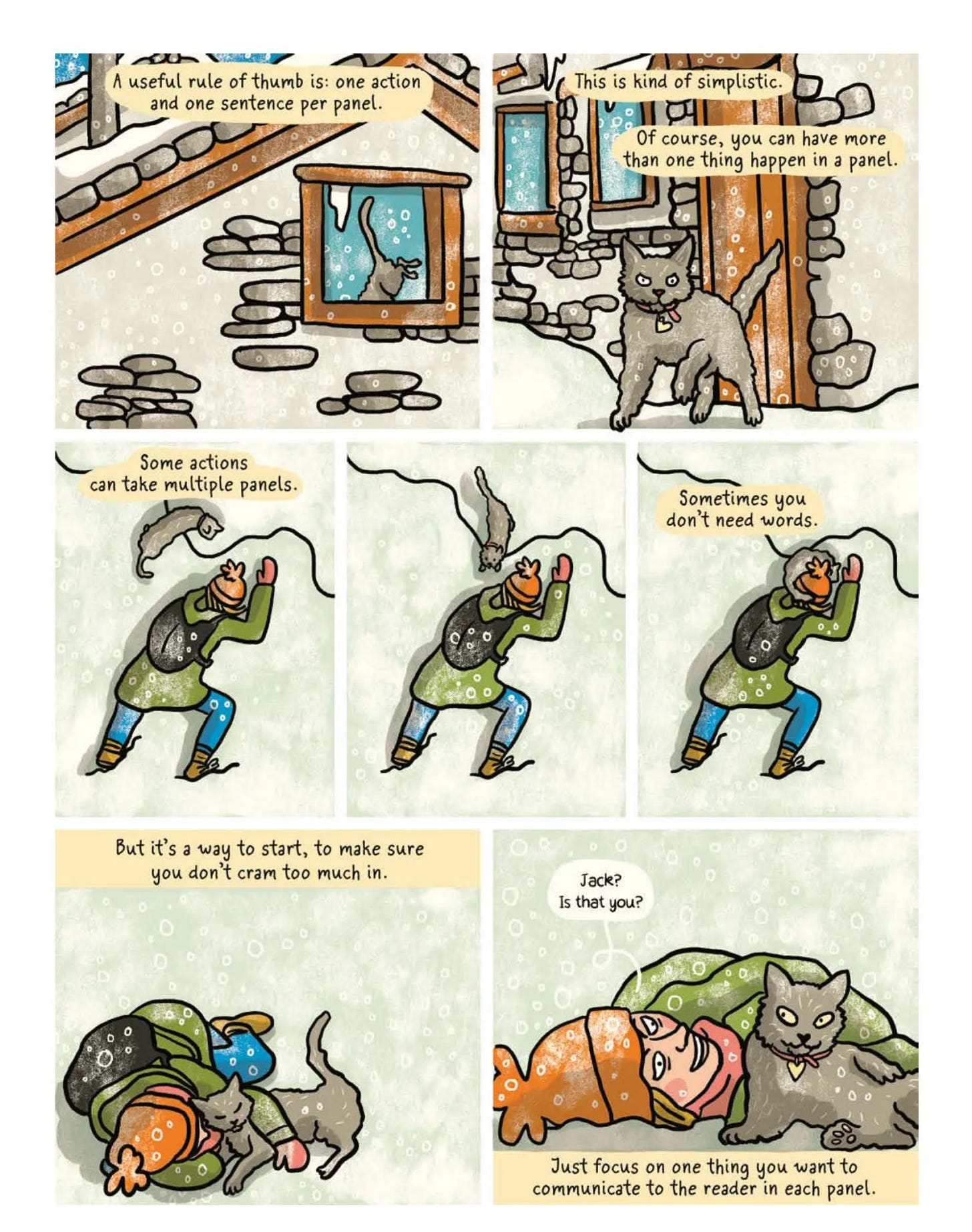

The book is fantastic, offering clear instruction in comic form—the comic avatars of Eleri and Shay are welcoming and knowledgeable, active and encouraging. The two also present interviews with a number of folks in comics, such as Thi Bui and Joe Sacco. And, sprinkled throughout, there are helpful “Skill Share” pages, which highlight and breakdown specific comic-making techniques (one is highlighted below).

We are very happy to interview Eleri and Shay, and encourage everyone to add Making Nonfiction Comics to their shelves.

You both come out of years of work at the Nib and other comics journalism outlets. When you sat down to make this book, what did you feel was missing from existing resources like McCloud’s Understanding Comics or Lynda Barry’s Making Comics that you wanted to put on the page for nonfiction creators specifically?

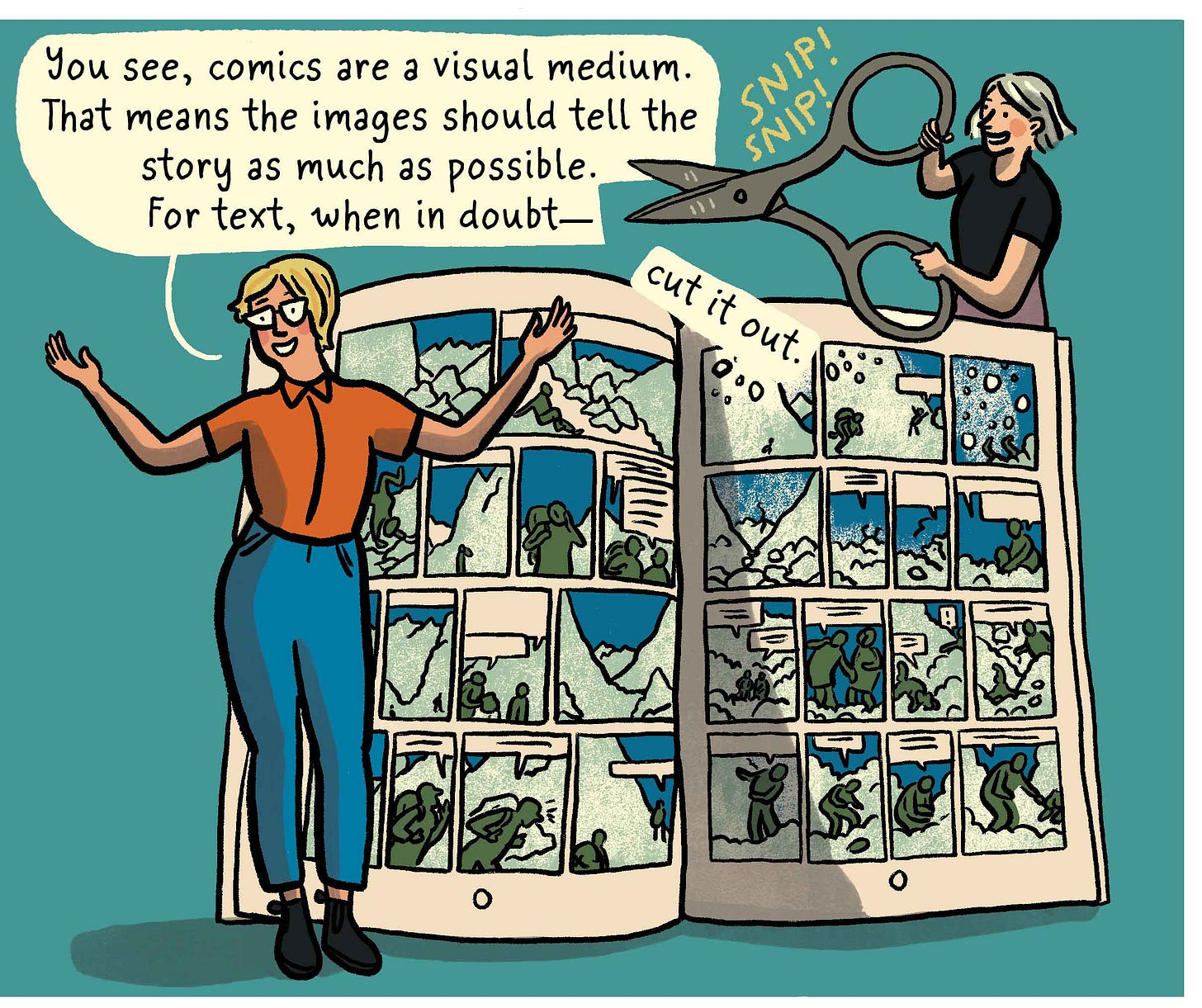

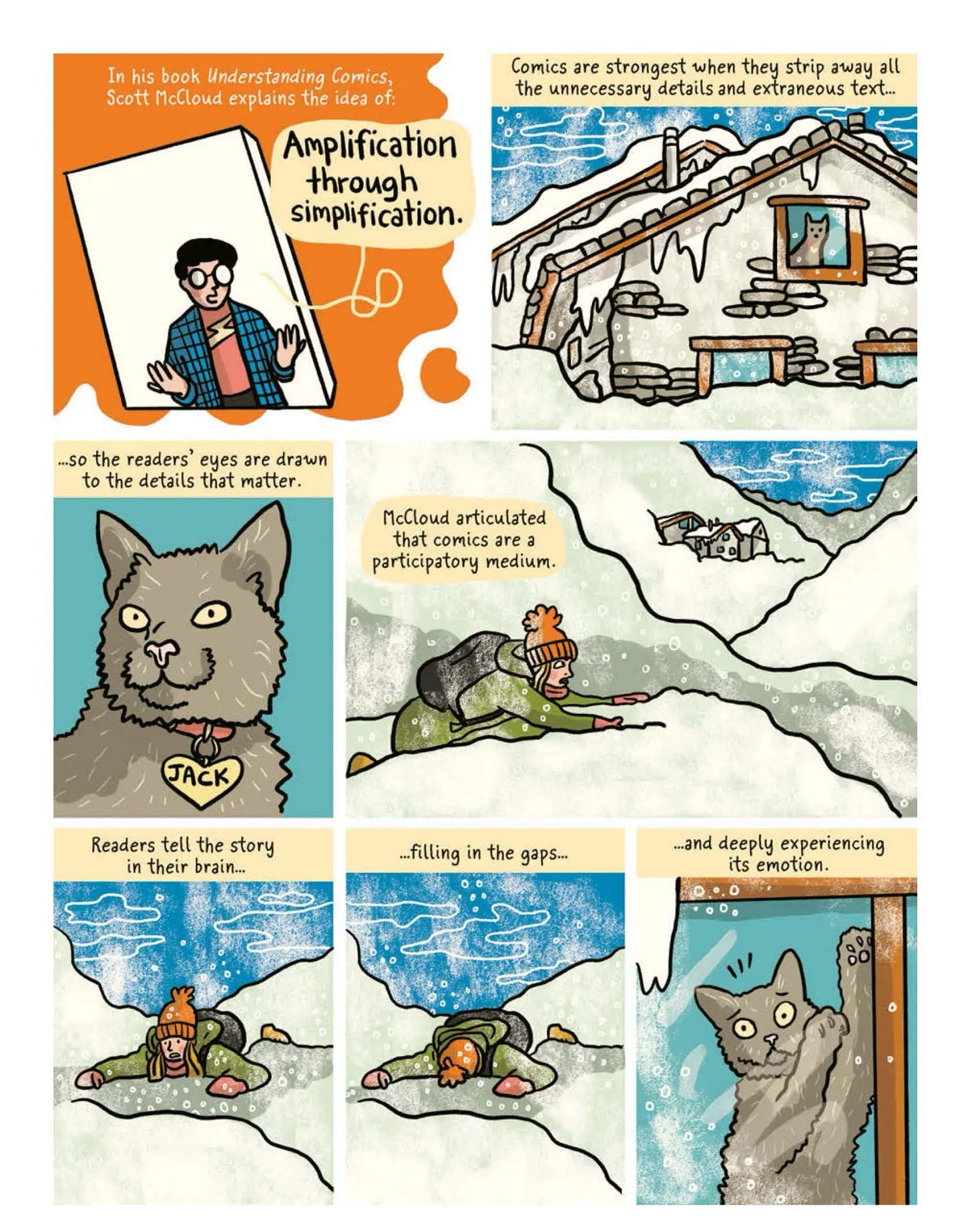

SHAY: I love both Understanding Comics and Making Comics, they’re really insightful books that I often use when I teach my class on making memoir comics. Understanding Comics helps readers understand how comics work and provides a lot of the language we use to discuss comics, and Making Comics is full of helpful prompts to get your brain working creatively and to see drawing and writing from new perspectives. What we wanted to add to that canon is a book that walks readers through step-by-step how to make their own nonfiction comics. Because of our work at the Nib, Eleri and I are often contacted by people who want to make nonfiction comics but aren’t sure how to approach the process, which can feel overwhelming and intimidating. A lot of researchers, journalists, and people hoping to write memoirs get in touch asking for help and guidance. So we decided to make that guide! Also, we wanted this book to showcase a bunch of different visual styles and approaches. Every artist makes their comics in a slightly different way. We interviewed 40 artists for this book, to show a diversity of visual styles and techniques. Hopefully people come away from the book with dozens of new artists to inspire their work as well as an empowered feeling of being able to dive into their own nonfiction comics project.

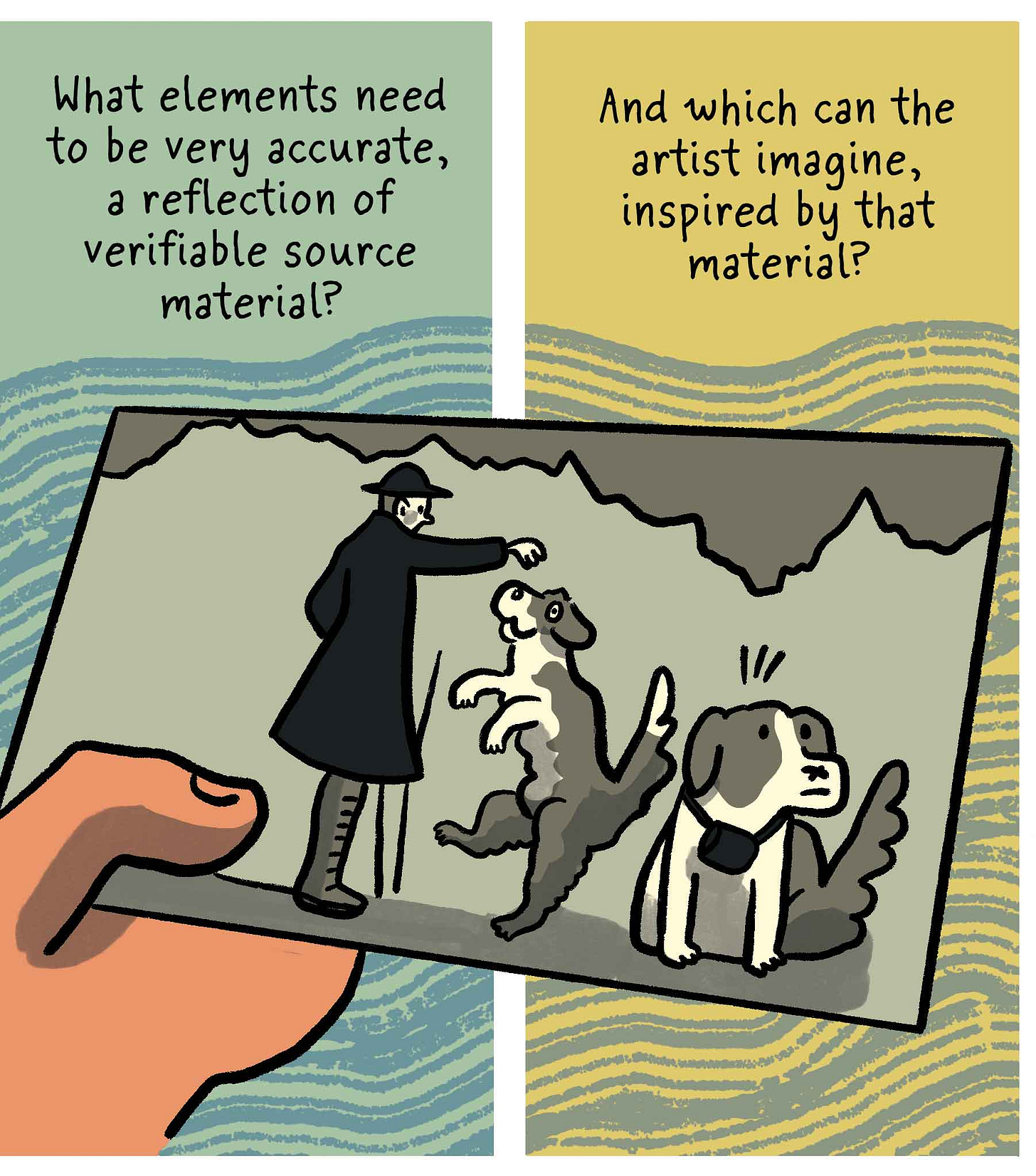

ELERI: Some of the things we look at simply aren’t going to be covered in a book that’s just looking at comics making. In Making Nonfiction Comics we go through the ethics and practice of interviewing with the explicit intention of creating sequential work. We ask sticky questions about power relationships with the real life people who may feature in your comic and go through safety precautions if you’re going to a protest. We also discuss different approaches for research, including visual research, because it’s important to understand copyright laws and proper sourcing of materials when you’re making anything nonfiction. Technically in nonfiction comics there are no rules, but we think it’s valuable for creators to consider the ethical implications of the choices they make when guiding their readers through real world experiences and issues.

How did your experience on projects like Guantanamo Voices and shorter comics for the Nib shape the practical advice that made it into Making Nonfiction Comics?

SHAY: I really learned how to write nonfiction comics at the Nib and then putting together Guantanamo Voices was a crucible—I had to take very complicated stories and figure out how to tell them visually on a tight deadline and with a limited page-count. That experience was super helpful in making this book because we had *so much* we wanted to say and figuring out how to squeeze it into the limited page-count was a puzzle. One place you really see that experience come through is there’s a skill-share page called “Three Perfect Panels” that’s about three punchy ways to begin a comic. Each approach is a way to grab readers’ attention quickly. As much as artists want to meander to their point, especially if you’re publishing comics online, you have to keep in mind that the audience’s attention span is limited so they need a compelling reason to dig into your comic.

ELERI: I edited over 1,000 nonfiction comics essays and shorter pieces in my decade at the Nib and I feel like the creators I worked with taught me so much. Even though I have authored many of my own nonfiction comics, a great deal of the bigger questions I faced and lessons I learned were from working with other people. Questions like, where did this image come from? Is this a reliable quote? How should I structure this so that people easily understand this complex story? We always went in with the goal of helping artists make the best possible comic they could about their subject or issue in the space and time they had — and honestly we all made a lot of mistakes! Part of what motivated me to create this book with Shay was so others could learn from our experiences not just as creators, but also as editors. Over time you get better at gauging for yourself what’s going to work and what won’t, but Making Nonfiction Comics provides information for creators on best practice in this field so they can start from a higher point of knowledge and understanding.

This book has so many great interviews in it with comics creators. Are there any interview responses that surprised you or got you thinking about nonfiction comics in a new way?

SHAY: We interviewed about 45 artists for this book, so there’s a lot of great moments. But the interview I think back to most often is the one with Fahmida Azim about representing violence in comics. Fahmida was part of the team that won a Pulitzer Prize for telling the story of a Uighur woman who escaped a Chinese prison camp. She speaks really clearly about how you can balance showing real-life elements of violence—like a police officer grabbing her hand or shoving someone into the back of a van—without drawing explicit, gory moments that might traumatize readers or make them feel like they’re reading a sensational horror comic. Fahmida describes how focusing on details can evoke the images’ in readers’ minds and get them to imagine what happened outside of the panel. I think about how to do that in my own work.

ELERI: Conducting the interviews for this book was such a joyful experience. I feel like Shay and I were constantly chatting afterwards about the unique practices and insights from the artists. There are so many things I took away from them, but what comes to mind is how much I loved hearing about Lebanese artist Ghadi Ghosn’s practice of making each individual panel its own visually spectacular element within a sequential piece. Basically, make every moment of the story count. No panel need just be utilitarian, it must also be beautiful and meaningful to the story. I’ve thought about this lesson from Ghadi a lot and certainly it shaped my art for our book.

How do you see this text pairing with the work you are doing at Crucial Comix and the community-building you do (I’m thinking of your cool bicycle zine library)?

SHAY: Yes! I do have a zine bike, which is usually parked in front of my house as a free zine library, and I also ride to events to give away zines for free. The heart of both Crucial Comix and this book is building an ecosystem of artists supporting each other. So many cartoonists are out here on our own, figuring out how to make a living and survive, I want to create more spaces where we learn from each other. So Crucial is a teaching press—cartoonists teach classes online and get paid, but some of the money goes back to the press to fund publishing other artists’ work. And in this book, we want it to feel like it opens a door for readers. You can read this book and learn about the work of artists all over the world, and be inspired to join them.

ELERI: I moved back to Australia during the pandemic in 2020 and much of my work in community building has been focused here, particularly with the Comic Art Workshop (CAW). This is a two week long remote residency for cartoonists embarking on ambitious comics projects. I was the co-director of this grassroots organisation for three years, but I’ve been attending since 2015. Over time we’ve built an amazing community of artists all over the country and abroad who help each other out on projects, create events together and genuinely just use their friendships and connections for the greater good of the whole. Without the support of friends from CAW I think I would have struggled to readjust to working in Australia. Being involved with a community really enriches your life as well as your comics practice!

If you are interesting in reading an excerpt of Making Nonfiction Comics, you can check this page out at Crucial Comix.

Purchase Making Nonfiction Comics directly from the writers here.