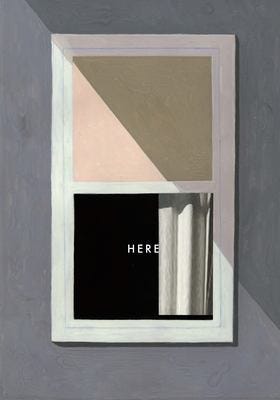

Here, Here

An exploration of Here the graphic novel by Richard McGuire and the 2024 film adaptation

Hey everyone, if you wanted a movie adaptation of the unconventional, seminal, “architectural” graphic novel Here by Richard McGuire from another Richard, longtime director R. Zemeckis (Forrest Gump, Who Framed Roger Rabbit? and many other crowdpleasers); we have got good news for you—it exists! And, it came out to little fanfare (and some pretty negative reviews) in 2024. Here at Autobiographix, in the dog days of August, we were interested in the choice to make McGuire’s groundbreaking work into a mainstream movie and wanted to explore the relationship between the two.

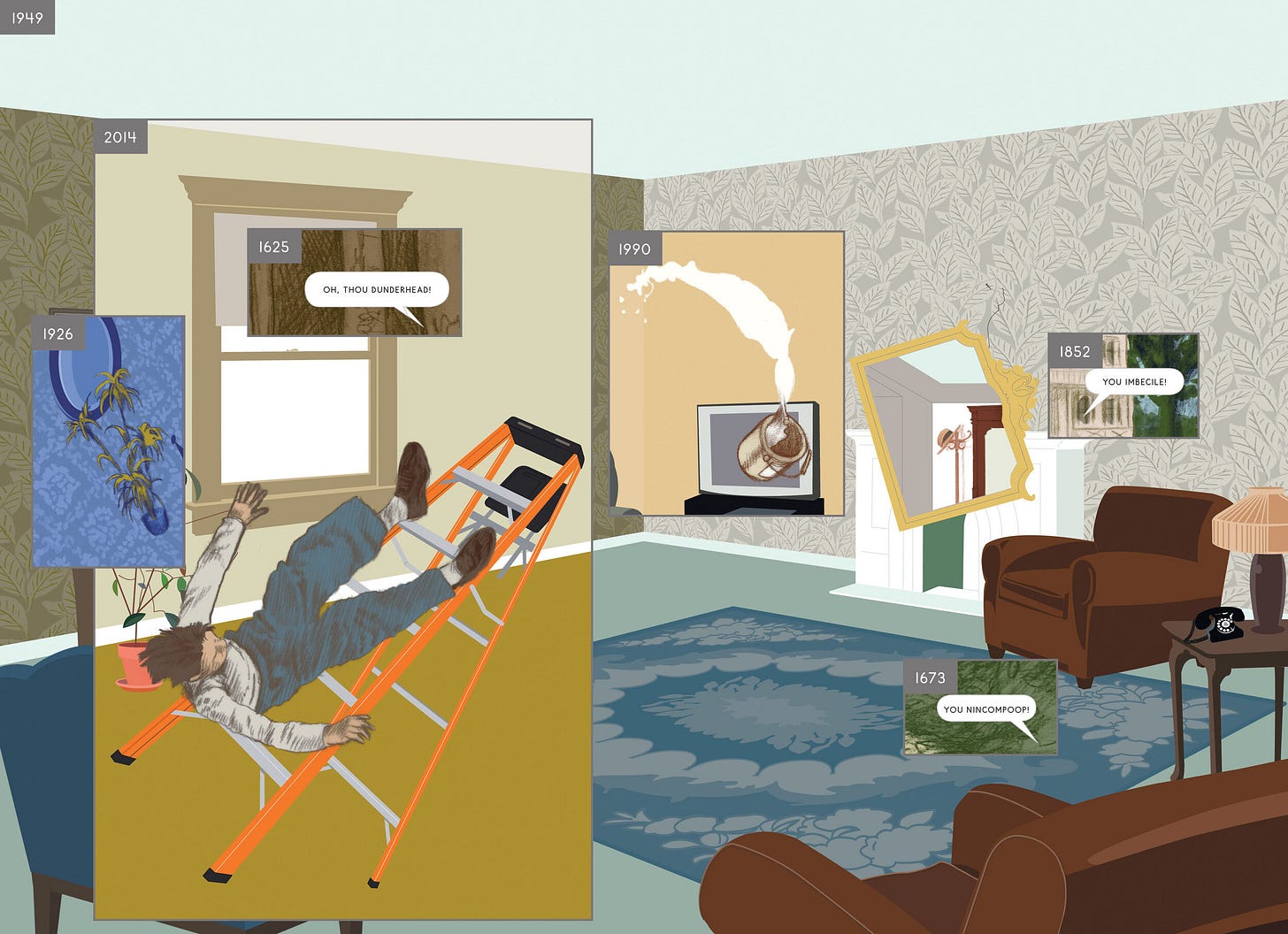

McGuire’s book lays out the phenomenon of inhabitation: When we walk into a room, we are confronted by our memories of the room in addition to the room itself. We experience it in an atemporal way, with layers of remembered space blurring across the current experience of space, whether conscious or not. There is no specific reality of the space: it is all temporal instances of the space collapsing. In Here, McGuire takes this phenomenon one step further and shows how the hugely distant past and more recent past echoes in the current space. He also opens this echo to show the potential futures of the space through inset panels.

Here feels like a graphic novel that the phenomenologist Gaston Bachelard would have loved. As Bachelard says in The Poetics of Space, “thus the house is not experienced from day to day only, in the thread of a narrative, or in the telling of our own story” (27). McGuire echoes this tension of simultaneity vs. succession in using the comic medium itself—the images are both static and sequential, yet their sequentiality operates differently than our “standard” forward-and-back motion comic. The boxes revealing the activity, or stillness, of various time periods feel stuck in some huge cosmic web, where most of the scenes he chose to depict will inevitably be digested, excreted, and forgotten.

Nora’s take on the graphic novel grew rather gloomy, perhaps because she has not lived “here” for more than four years since college. What does “here” mean when you don’t know a place very long? As Nora and Amaris talked, we felt that Here reads as anti-autobiographix, in that it renders a person’s story more or less insignificant—we are all moments about to collapsed into the million other moments behind and ahead of us. It made Nora a bit depressed but also relieved in a way—does it matter what happens? A dinosaur once breathed where you do, and 100 years from now a hologram could give a tour of the (now-rendered-by-climate change) marshland where you once ate a bowl of cherries (and no one in this future space knows about this delicious bowl of fruit!). How does our understanding of a never-ending spot make us think about the boundaries of the limited self?

In this anti-story way, the graphic novel is a significant achievement, but made for an even more perplexing choice to make into a feature film from the guy who also made Castaway.

The movie Here fights this anti-story impulse by creating stories. We found these, often, to be emotionally manipulative, with too much de-and re-aging AI blurring familiar actors’ faces (and yet, Tom Hanks still does not believably pass for a teenager). The manufactured plot is a bummer—none of the main characters ever attempt to take agency of their own stories. The heavy-handed acting and depictions of different eras jarred: the time periods feel too telegraphed in how the space is set up across eras, as well as the writing with lines like “gee whilikers!” and the characterizations of the repressed, hard drinking WWII veteran, or the sourpuss face from the dour Victorian wife. The filmmakers used the same formal conceit as McGuire, using outlines of boxes to show “windows” into past time periods while the present occurred. We were at least glad to see this technique, as it offered something different from other films exploring concepts of time.

The book also captures a sense of playfulness and has a sense of humor, but the movie is trying to be quite serious, to its detriment. The visual punchlines of the book are clear and satisfying. There are several scenes of costume parties, which add levity. And, stylistically, the book is very impressive, immersing the reader in subdued washes of color and unique details of different eras. Comparatively, the movie feels more like a stage set than anything innovative.

Is the book more successful because we never latch onto any of the characters–none of them are main or secondary (except maybe Benjamin Franklin, who appears with all his attendant familiarity)? Or, is the book just more honest about the lack of meaning-making in its project? The movie tries to make meaning from what McGuire’s book essentially proves meaningless—each of our lives. The main character in the book is that living room corner, that spatial anchor, that stage for all the possibilities of living across time. Bachelard could go on and on about the phenomenology of that corner. That is the success of the book, of showing a place as witness, and simultaneously the downfall of the movie. In that way, the adaptation serves less as a companion to the book than as its counterargument: that what matters most in Zemeckis’s Here is not the place at all, but the people passing through. Whether that feels like an expansion or a diminishment might entirely depend on how long you’ve been standing in that corner.

That is WILD that they made a movie inspired by this comic. Really interesting to hear your take on both of them. I thought the book was fascinating to think about but can’t imagine it working as a movie with a story. It was more like a think piece or a sculpture to consider as opposed to something asking for stories…

"we are all moments about to collapsed into the million other moments behind and ahead of us." Wow! Well put!

That reminds me of John Locke's concept of psychological continuity with memory defining one's identity.