In July, I had the pleasure of temporarily escaping the heatwave in New Mexico and heading up to Toronto, Ontario, to the Graphic Medicine Conference. Graphic Medicine explores the intersection of comics and the discourse of healthcare, and I had been wanting to attend the conference and learn more since hearing about it from a friend.

It’s rare to find many truly interdisciplinary spaces, but the conference was just that: a place where traditional disciplinary boundaries dissolved. The Graphic Medicine International Collective describes itself as “a community of academics, health carers, authors, artists, and fans of comics and medicine.” The combination of researchers and medical professionals and artists and storytellers produced a community that was intellectually sharp, inquisitive, and caring. When health, illness, disability, and caregiving take center stage in artistic inquiry, you would expect nothing less.

The beauty of comics is that it is that, in many ways, it is interdisciplinary—comics demand an understanding of multiple domains to be effective. As explained by Will Eisner, the “godfather of comics,” in his book Comics and Sequential Art, Will Eisner writes that to create comics, you need to grasp:

Psychology – human interaction, body language, social values, cultures, mores, history, literature

Physics – light, gravity, air, water, motion, force, how things work, mechanics

Design – employment of space and shapes, stagecraft, calligraphy, clothing, costume, architecture, printing process and digital reproduction

Language – vocabulary, plotting, myths and imagery, playwriting

Draftsmanship – human anatomy, perspective, color, caricature

And yet, as Andrew J. Kunka explains in Autobiographical Comics, comics offer something different from other media. Kunka writes that comics do “not present documentary evidence in the same way that other media can, like prose, photography, and film. [...Because they are drawn…] the autobiographical experience is more transparently filtered or mediated through the artist’s consciousness and style.” Whereas photography and film have traditionally been understood as more “objective,” comics are obviously subjective. Graphic medicine, then, presents a powerful tool to articulate, explore, and understand the nuances of health experiences. It leverages the subjectivity, expressiveness, and multidisciplinary nature of comics to bring forth a more humane and compassionate approach to healthcare discourse.

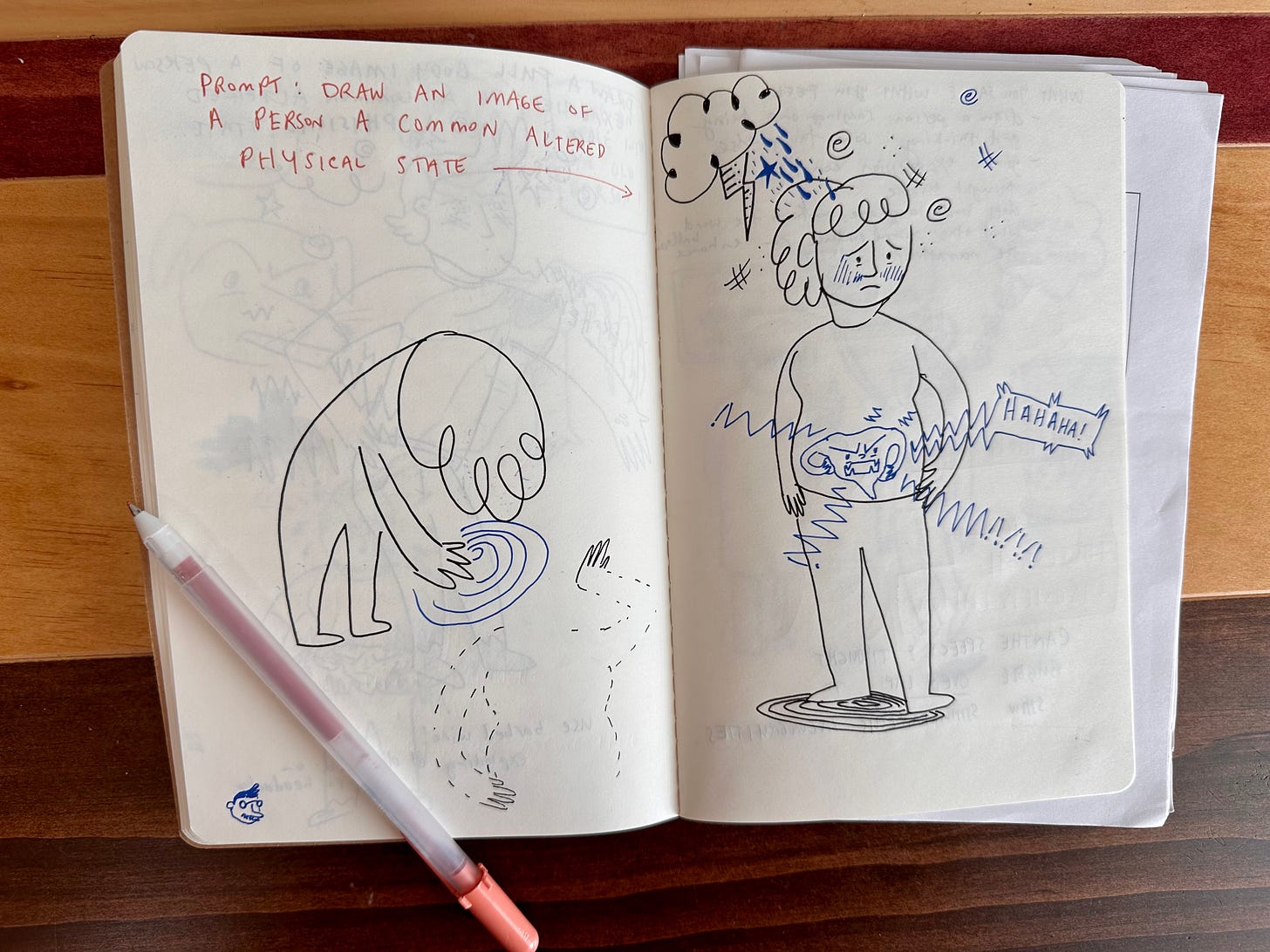

My personal experience with health-related comics started when I began creating my own to explore personal health issues. While working on that project, it was the cancer journey of my spouse, though, that brought the potential of diary comics to light. Over the past year, my role as an "Artist-in-Medicine" at the university cancer center has allowed me to experience first-hand the capacity of comics to communicate, unpack, and aid in healing from medical experiences. I spoke about diary comics as mindfulness (and will probably write more about that later), and I was struck by several presentations on visual autopathographies, which might be described as patients’ attempts to express their own narratives about illness (I guess the the “case history” was invented by Hippocrates—and since, has often left the person out of the tale of their own body)—from timelines to personal anatomical journals, to drawing the objective and subjective states of health (such as symptoms, or the felt expression of illness).

The conference was a mix of lightning talks (on subjects as diverse as bunion surgery and Canada’s “Baby Scoop Era”), paper presentations (such as graphic medicine in dementia care and drawing pandemics), comics workshops (including drawing health landscapes, comics to help you prepare for death), and keynote lectures and dialogues (graphic medicine and generational experiences of Moose Cree First Nation health research). The program was filled with such interesting variety that it was difficult to decide what to attend—and thus what to miss out on. I suppose this means the conference was a good size, but I feel like I both learned a lot and missed many presentations and workshops that I was curious about.

So, I spoke with a couple of the attendees and presenters about what draws them to graphic medicine and what their biggest takeaways from this year’s conference were.

Dr. Robin M. McCrary, who teaches writing and composition in the Health Humanities program at Syracuse University said:

What draws me to graphic medicine is its utility. I’m not a creator/artist myself, but I love using graphic medicine as a teaching tool in (public) health humanities. It has been great watching learners engage, for example, with Meredith Li-Vollmer’s work or with Michael Green and Kimberly Myers, toward the benefit of their own research agendas.

My biggest takeaway from the conference is about how diverse graphic medicine itself is. I got to see the wide variety of ways others engage with graphic medicine—whether talking about its use in bystander CPR training (Annika Mengwall), in medical interpretation (Maja Miłkowska-Shibata), or in so many other ways.

Comics creator Jen Leach (who also makes so many rad things, including cat toys) told me:

Graphic Medicine has given me a voice to reclaim my experience as a patient and my identity as an artist! Graphic Medicine welcomes all—scholars, artists, patient advocates, librarians, clinicians, and many who hold multiple roles. The form allows us to “read” between the words and the images—to insert our own experiences into the invisible thought bubbles...it provides an accessible entry point, an invitation to difficult conversations about illness and health.

I was really moved by Lisa Boivin's keynote, Arranging Pretty: Piecing Together Medicine Dreams. Her gorgeous collages depict the loss of a loved one and the strength and wisdom we can find in nature (which takes the form of Bear, Hawk, Caribou, and Wolf).

I also enjoyed walking down Graffiti Alley with old and new friends (and getting to meet Amaris, who I have known since 2021!). It's fun to go all the way to Toronto to hang out with people I never see back in NYC!

Lara Antal, whose collaboration Ronan and the Endless Sea of Stars won the Graphic Medicine book award, said:

I came to graphic medicine through collaboration: I translate other peoples’ experiences into comics. It’s an honor to hold their stories, each so potent, precious, and complicated, and order them into narratives readers can understand or feel. I love graphic medicine’s ability to transform these personal, internal experiences into something people can interact with.

The Graphic Medicine Conference showed me the breadth of what this field can be, but also how much deeper it can go. I feel drawn in two directions; comics as an active tool to help patients and families, and comics as a way to express the nuanced, intangible moments of health.

All in all, it was a great conference—and of course, Toronto is a great city for comics-lovers. Perhaps we’ll see you at a future Graphic Medicine Conference!

The Graphic Medicine International Collective works hard to share graphic medicine through a podcast, a newsletter, a spotlight section of the website, comics reviews, an online workshop called Drawing Together, a book award, a small travel grant, a syllabus exchange and repository, and of course, the conference.