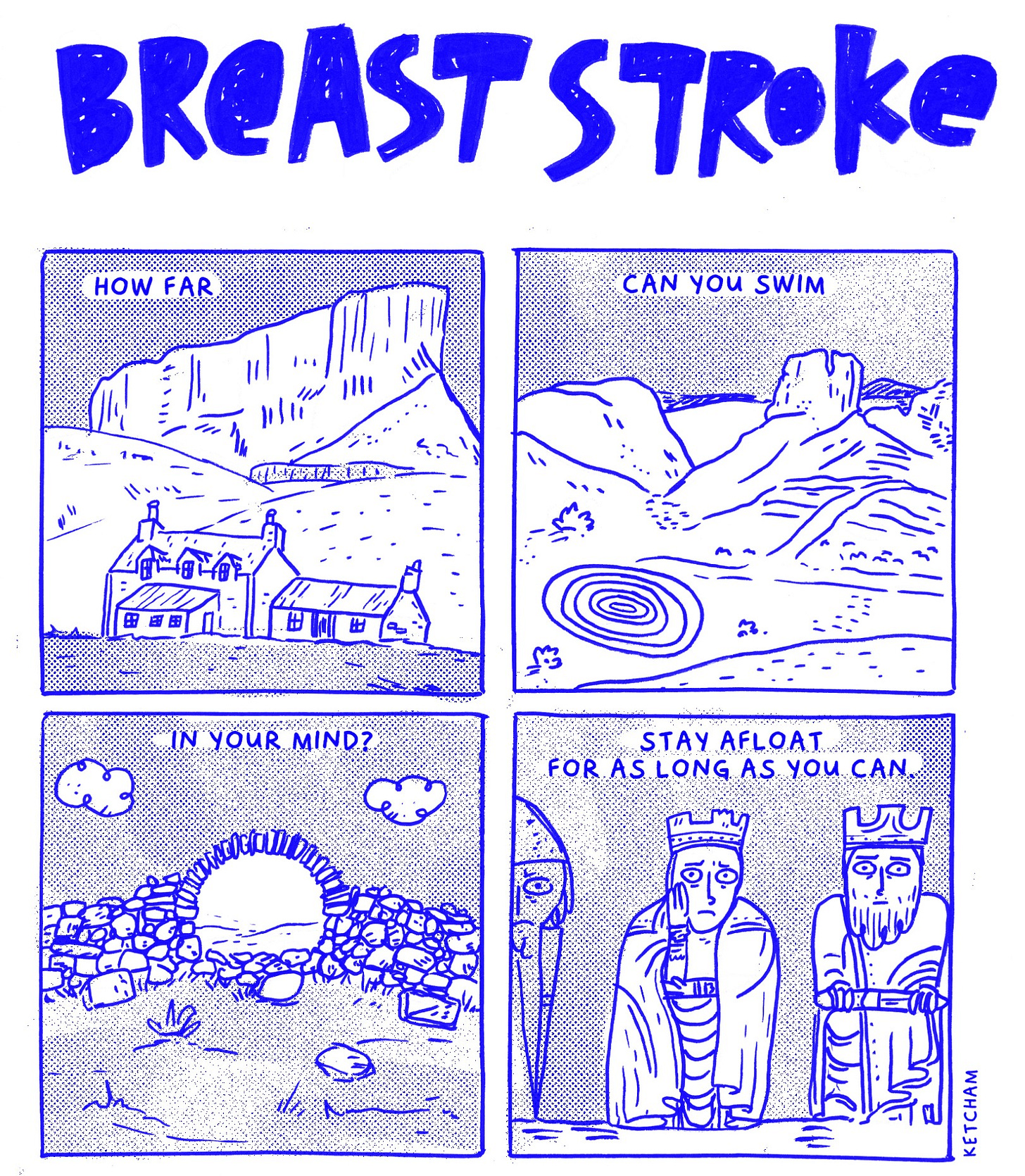

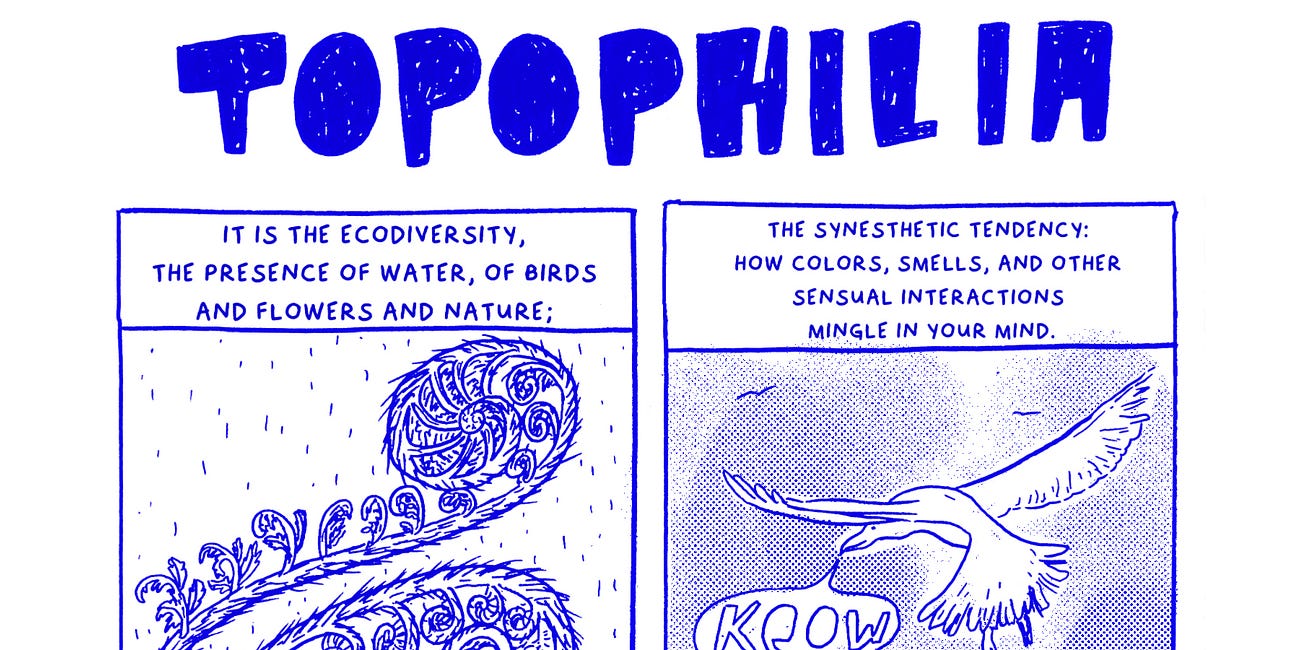

In a few days, I will be on a plane to Scotland to teach a short, place-based creative writing course. Scotland, and the weird little comics I have been making about my time there last summer, is a big part of the reason I have been thinking about comics and how they describe and relate to a particular place. In the first post in this series, I discussed the difference between background and setting and in the second, I considered the effect of place-based language to enhance an immersive reading experience.

In the course I am about to teach, I will be reminding students daily about the power of observation. It is the cornerstone of every academic discipline—and it is impossible to be observant while looking at your phones all the time. One of the ways that I am having them practice observation is using the Lynda Barry method of recording 7 things you did, 7 things you saw, 1 thing you overheard, and 1 question of the day. Last summer, I started thinking of this diary method as similar to Fluxus poetry, creating a potential space to break down the boundaries between art and everyday life, a kind of “counter spectacular” writing. It embraces chance, everyday actions, and lived experience into a potential comics-making method that resists the more polished, curated versions of experience we might see on social media or traditional literature. When you have kept this kind of diary for several days, you start to notice what you notice—the kinds of things you are drawn to. They become the creative’s field notes for sensory experiences of a place. After our study abroad, revisiting these recorded observations can reawaken curiosity, allowing even the mundane to take on new meaning. Of course, my students also had their phone cameras and, I am sure, too plenty of photographs that they can revisit when writing about a particular setting.

It helps if you can visit a place, make observations, draw sketches, take a thousand photographs, collect ephemera like postcards and brochure, do texture rubbings, create a color palette, etc., but what if you can’t? I have been brainstorming some ways to do visual research without being present.

Archives and image databases

Museums and libraries are great resources for photographs, illustrations, manuscripts, maps, and other ephemera. Here are a couple of bigger ones to get you started:

The Library of Congress has several sets of photos you can browse through.

Google images is always good, but so is Google’s Arts and Culture database.

JSTOR developed a companion site called Artstor.

If you are looking for scenes from a particular country, you can also visit their national library.

In Syllabus, Lynda Barry shares a drawing assignment to sit with an image of a group of people posing. It looks like a snippet from a high school yearbook or a small town’s newspaper—other potential local sources for reference images. You can get creative with exactly what your archives are.

Google Street View

The Sequential Artists Workshop had a fantastic Friday Night Comics workshop with Alabaster Pizzo, who walked folks through her method of using Google Maps and the “street view” setting to help draw establishing shots and backgrounds. “You think you know what a place looks like” but a good reference photo will have details that you may have forgotten, Pizzo says. She has several great tips, like

finding an apartment for rent in another city through realty listings (or a vacation rental site),

using street view to take an imaginary walk from that apartment to get a bite to eat,

clicking on a restaurant or store to view the 360-degree views of the interior in Google Maps,

typing a location name into Instagram to see the photographs folks have tagged,

not tracing—and not worrying about drawing every detail: “Simplify in a way that works for [your style].”

Google Maps can also reveal some occasional surprises…

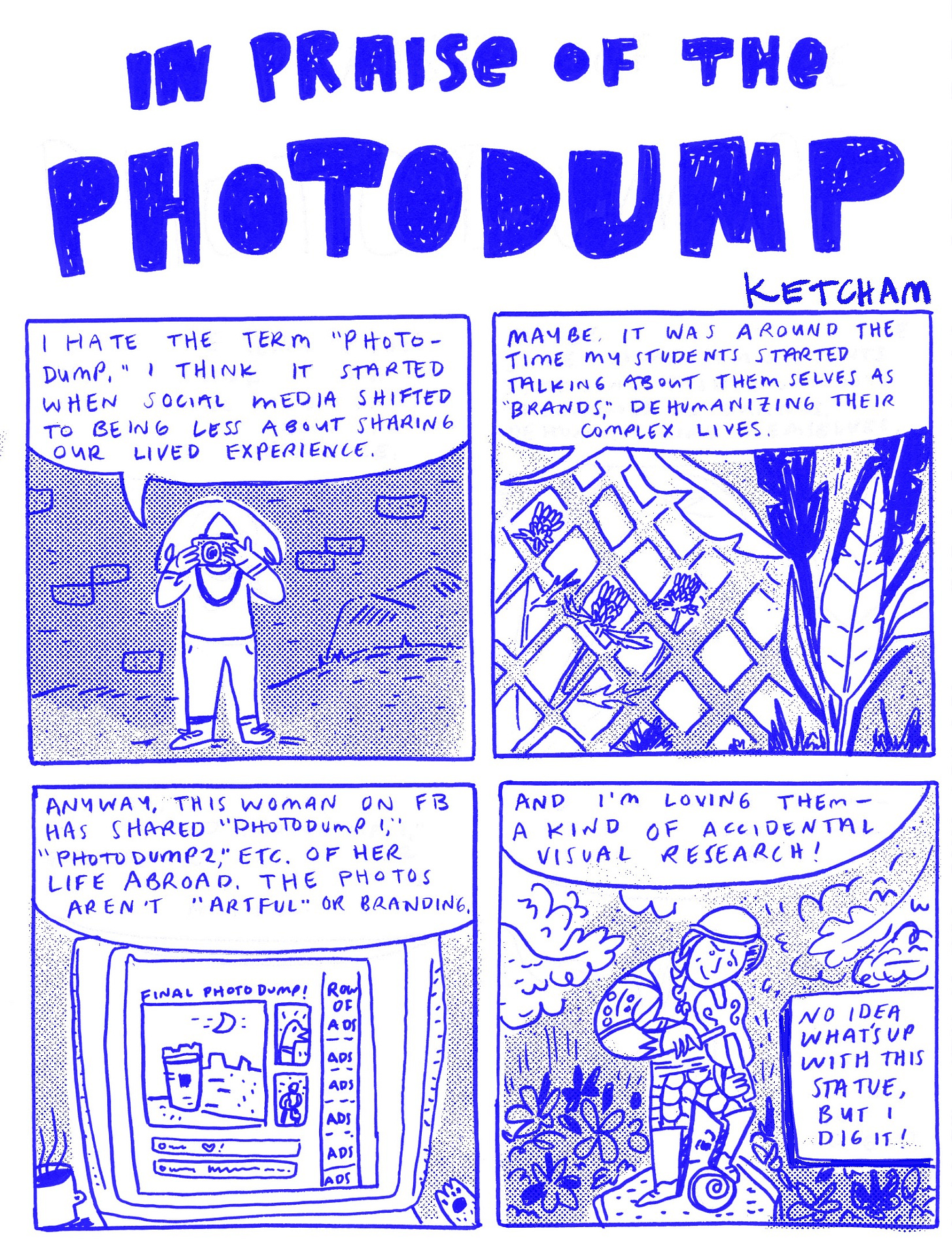

“Photodumps” from Friends on Vacation

There’s something interesting about mixing memory with found imagery to create a personal comic—the complexity of writing about lived experience using archives has been a hot debate in creative writing circle since Vivian Gornick’s The Situation and the Story was published in 2001. But the eclectic nature of visual research, enhanced with a virtual stroll through a map means that you don’t have to sketch street scenes on location to render a world on paper. I’m sure there are a dozen other ways out there to dive into visual research that I haven’t considered for this post (have some ideas? let me know in the comments!), but the most important part is to keep your eyes open and sketchbooks ready!

If you missed the first posts in this series:

For the Love of Place

We spend so much our time placeless. For at least eight hours a day throughout the week, I’m in my email inbox, spreadsheets and reports, shared documents, learning management software, InDesign, and social media. I’m at the computer and the world falls away; I’m on the couch with the phone in my hand, not present even in my own house. My mind looks at …

Comix and the Love of Place

When I first started making comics, I came to writing the text the way a poet might: in my expository text and inset panels, I worried about enjambment and line breaks. I thought a lot about the economy of language and concise sentences. I realized I oft…

Yay thanks for finding that workshop. That was a GREAT one, and Alabaster Pizzo is a star

https://www.alabasterpizzo.com/

:)

Oh I am ALL ABOUT Google maps !!!!