This week we are presenting at the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association Conference in Albuquerque. Here’s a little preview of our presentation for those of you who can’t make it.

What is the urtext of the travel-memoir genre–Homer’s Odyssey? Basho’s Narrow Road to the Interior? Kerouac’s On the Road? Few women populate the early recordings of travel. The beginning of the lineage of female travel writing is most linked to diaries, which also is a common comics genre.

From European vacations to hitchhiking adventures, bicycling across the country to wintering in Italy, the travelogues and memoirs of women comic creators reveal the joys and dangers of our desires to sightsee. They question our goals in travel while avoiding common cliches, and above all, strive to place the audience within the narrative.

We examined four complete travel comics to see how female comic artists use their medium to portray, complicate, and embody their experiences. We choose these particular books because they represent varying backgrounds, motivations, destinations, and styles.

An Age of License - Lucy Knisley

In this comics travelogue, Lucy Knisley embarks on a European trip that involves work, love, friendship and family, and trying to figure out her life’s purpose. If this sounds like a large scope, it is–and it mirrors the introspective and quotidian experience of many twenty-somethings as they stumble toward adulthood. She is invited to speak at a comics festival in Norway, meets a cute Swede who tempts her to Stockholm, and her mother welcomes her to France. There, she meets a man at a wine tasting who tells her, “The French have a saying for the time when you are young and experimenting with your lives and careers. They call it L’Age Licence. As in: license to experience, mess up, license to fail, license to do…whatever, before you are settled.” That comment becomes the title–and the main thread of the book.

This is a travelogue that is often more concerned with an interior journey of self-acceptance, of understanding a transition in life, than it is about situating the audience within a foreign place. While the audience always knows where Lucy is–and occasionally, what she is eating there–we rarely learn about the place, its history, people, or culture, or her experience of it.

It sometimes seems as though the dramas of her life are merely unfolding in a different location. For example, in France she considers the meaning of “L’Age Licence,” purchases some French food, then her mother brings up wanting grandchildren–all in a couple pages. Her travels are pleasant and lack the challenge and conflict that may perhaps elevate the place to a more central role in the narrative arc; thus it is the interior journey that becomes the story.

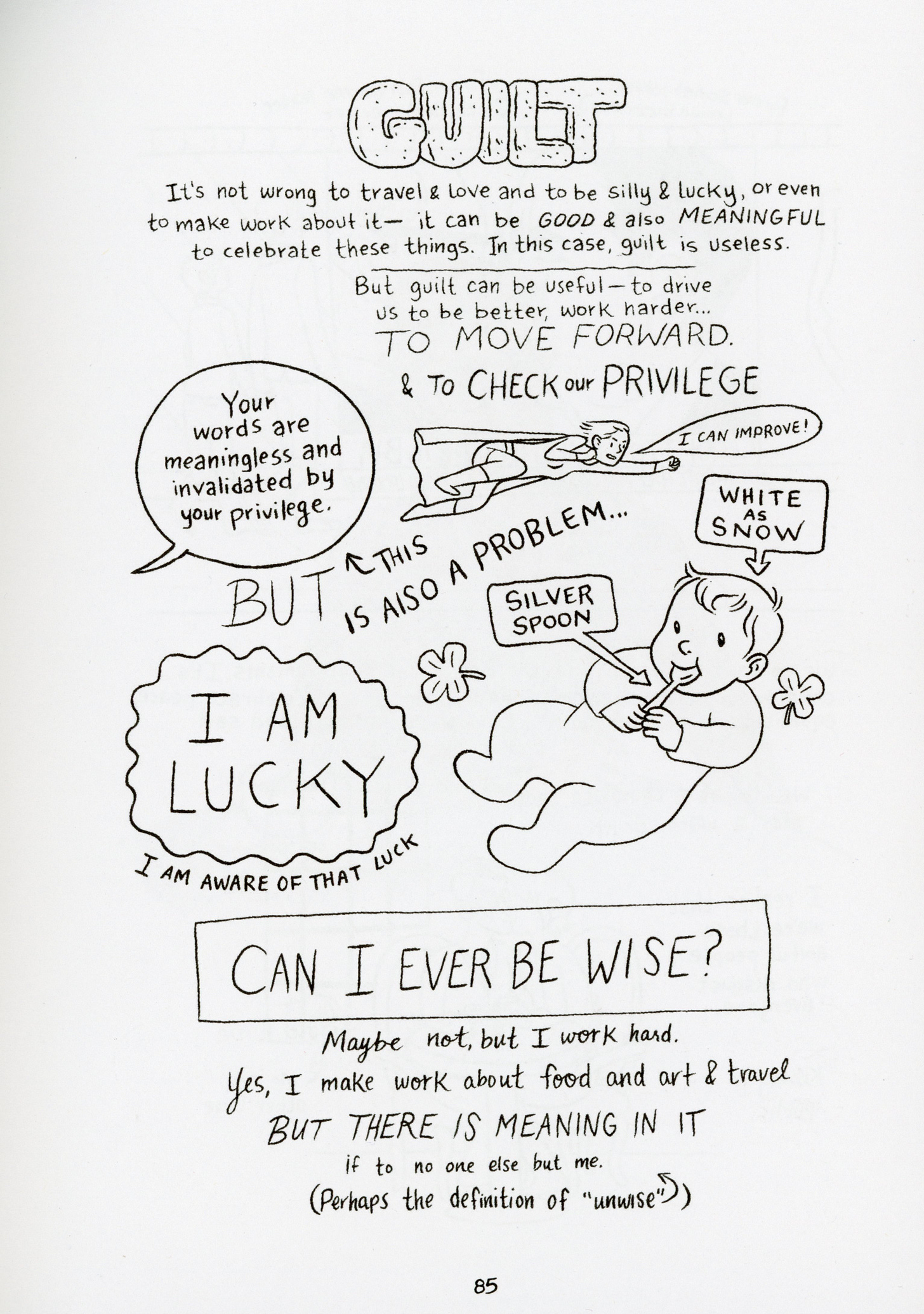

Throughout, Lucy is concerned with how the reader will understand this long trip across Europe. On the first page, she prefaces: “Through coincidence, work, and luck I was offered opportunities to take trips.” She argues with her Swedish lover about classism, and she feels guilt about her privilege–she’s white, lucky, born with a silver spoon in her mouth. She wrestles briefly with a question about whether she can ever be wise, but by the next page, she and the Swede are back to making out in a chocolate shop.

These ruminations of guilt and shame and privilege are never resolved, but linger along with her other epiphanies. Lucy’s revelations are youthful ones–that travel unhomes you and “allows you to see possibilities for change [and] growth,” “love is complicated,” and that she takes her freedom for granted sometimes.

Interspersed with these epiphanies, Knisely includes several diagrams and sometimes focuses our attention to a particular scene or item with a watercolor splash page–a full-page, full-color panel, sans dialogue. These splash pages show her range, both tonally and artistically.

Knisely’s panels are borderless, contained often by the page rather than a typical frame. As seen here, she often fills a page. Ditching the panels can help make the work feel more diaristic, less plotted and more off the cuff. Knisley also includes dates as we follow her trip through September, creating a conceit that these actions, epiphanies, and drawings happened in real time. As if to add evidence, she sketches herself sketching and we see a blurry watercolor scene, presumably her sketch from that moment.

Montana Diary - Whit Taylor

Whit Taylor’s Montana Diary may deceive at first glance: slim with an engagingly casual style, the mini-comic appears to be a quick and pleasant read about a recent trip west taken by the author and her husband. However, the reader accompanies Whit on what becomes much more than a straightforward road trip. As Whit watches Big Sky country unfold before her, she also ponders the meaning of the West–from its geographical to human history.

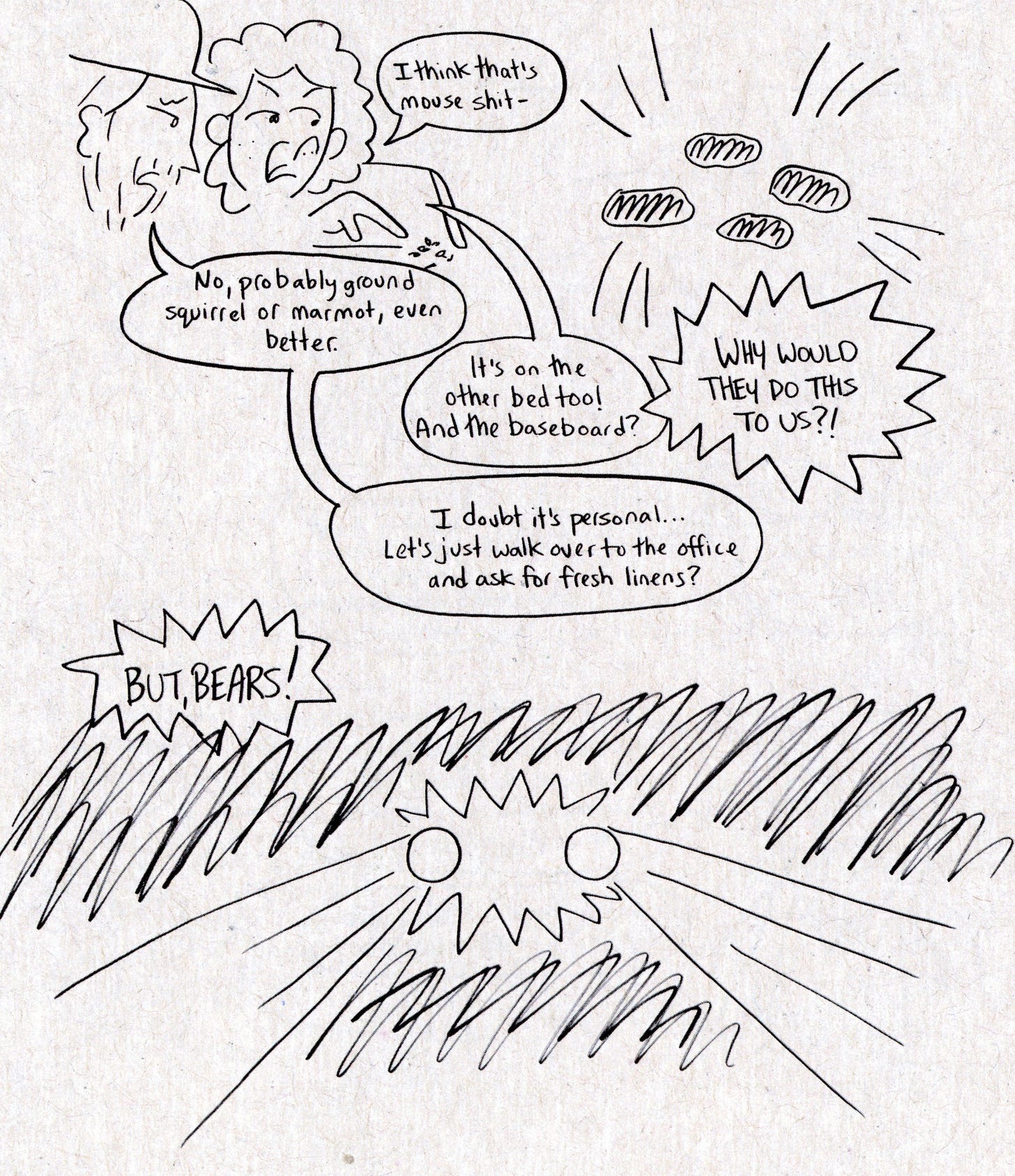

By the title alone, Montana Diary naturally evokes the intimacy and immediacy of a personal record, but the comic feels more akin to a nonfiction essay. And, a braided one at that, as Taylor layers her personal experiences like finding mouse poop and the ensuing fear of contracting hantavirus and contemplating traveling as a woman of color as well as the histories of where she visits. While acknowledging the enormity of the history of a place, land, and peoples, Taylor focuses on a few specific histories. She is interested in Lewis and Clark, and in particular, their relationship with and use of a “body servant” - York - and the better-known aide, Sacagawea. It is notable that Taylor plumbs recognized history from fresh, nonwhite angles as Whit herself is contemplating her place in one of the whitest states in the country. Early on in the trip she says to her husband, “I can see why White Nationalists like this place. They can pretend they live in Germany.” In her narration to the audience, Taylor notes, “I joke when I’m nervous,” and we see an anxious Whit glance out the window as they drive. By the end of the narrative, Whit reaches no easy answers about race in the West, but has found it to be a place where she does find beauty. Although the scenes she views evoke a racist (and sexist) past, she asserts her own right to be there.

The travel in Montana Diary is one of the most recognizable of our group of works in that the author is a tourist, looking for tourist experiences–with no shame. She wants to enjoy area delicacies, she takes guided tours, and visits National Historic sites. Taylor is probing the idea of America and the West via some of the most recognizable paths and figures, and yielding unexpected insights because of her honesty and position in society as she is “descended from slaves, slave masters, and native peoples.” Her interior journey is apparent from her reflections on the familiar sites of the West.

In such a short space, with simple lines and panelless scenes, Taylor achieves a remarkable amount of complexity, with digressions and revelations happening subtly. As she listens to a waiter discuss the night’s offerings at a local Montana restaurant (the elk short ribs are “a little odd-tasting”), she notices the seasonal workers smoking outside, which then leads her to ponder the hidden labor involved in the expedition of Lewis and Clark, leading her back to York. Her meditations on America, being a woman of color traveling in a Republican state, climate change, and the history of conquest are both heavy and humorous and always revealing.

Eleanor Davis - You, a Bike & a Road

The goal sounds so simple: bike from Tucson, AZ to Athens, GA. 1,800 miles. Almost immediately after writing this objective, Eleanor Davis layers the complexities of her motivations upon it: she wants to tackle the trip before she’s too old and her knees give out; before having a baby; because she is depressed. In You, a Bike, & a Road, Davis chronicles this bicycle trip by drawing daily comics. Each entry begins with the date, the travel day, the section of the route she covered and how many miles it was.

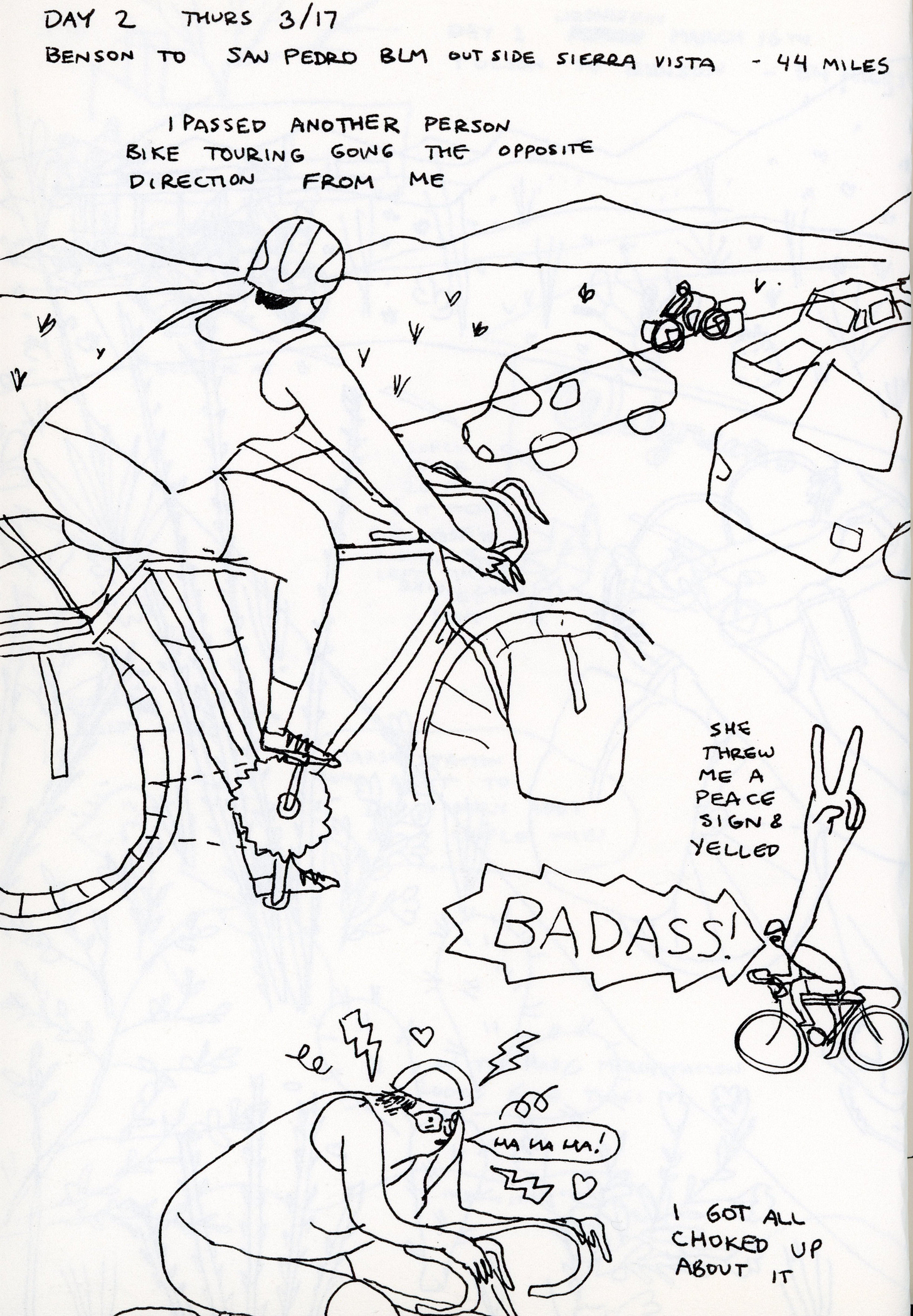

Early on, she passes another woman biker going the opposite way, who throws a peace sign and yells “badass.” Eleanor gets choked up about it, overwhelmed by the simple praise from a stranger. In addition to such simple moments of connection, the strangers Eleanor encounters show her great kindness. Moments of connection like this are peppered throughout the diary and show us the humble magic of the road.

Davis uses descriptive language, rare in comics exposition, as another way to let the audience into her experience. Rather than duplicate what she has drawn, the text instead describes aspects of the image that may not be readily seen, such as color or distance. For example, Day 16 has the note “Rocky pale mountains far distance, soft hills closer. / Sky deep indigo above, bright blue green on the horizon,” paired with just a couple horizontal lines.

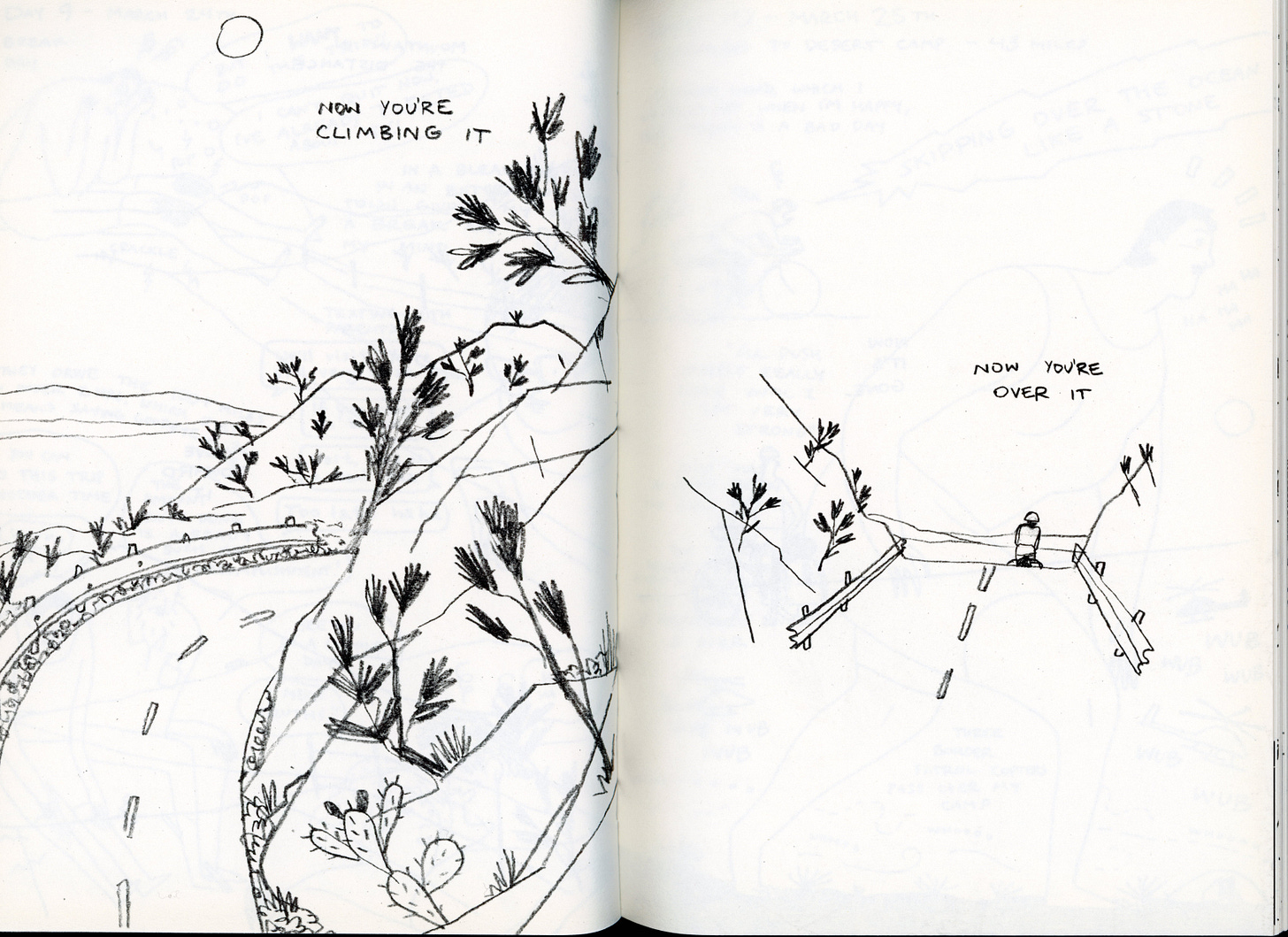

Using the second person and a habitual tense, Davis lets the audience inhabit this difficult and incredible journey. For example, Davis illustrates this trim text across four pages: “Mountain in the distance. Move toward it. Now you’re climbing it. Now you’re over it. Now it’s gone.” The economy of language here makes the text almost lyrical. Although Davis is describing the constant and repetitive challenges of the landscape during her journey, it can also be read as a metaphor. On the following page, Davis writes, “I’ll push myself really hard until I get very strong.’ This has always been my only plan.” You bike over the mountain and there’s only another, and another. You get stronger, but you can always be stronger still. Davis has a way of making even her most concrete reflections read as abstractions.

While some of the entries are drawn in pen, most of the work was rendered in pencil, which contributes to the audience’s interpretation that this is a raw, honest, and unfinished/unedited work. Pencil helps it feel like it really is a diary. Davis is expert at creating leading lines–where the layout leads your eye deliberately across the page– and creating full, dynamic spreads through her use of perspective and interesting angles. She draws her body so we know it’s a woman’s body but it’s never sexualized, even while naked.

Davis never makes it all the way to Athens, stopping 600 miles short. While Davis works so hard to draw the audience into the experience, it’s possible to finish the book without feeling as though one knows Eleanor. She provides very little context about her life–we are just in the moment, but we know little backstory, anything about her life outside of the timespan of this journey.

Ulli Lust - Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life

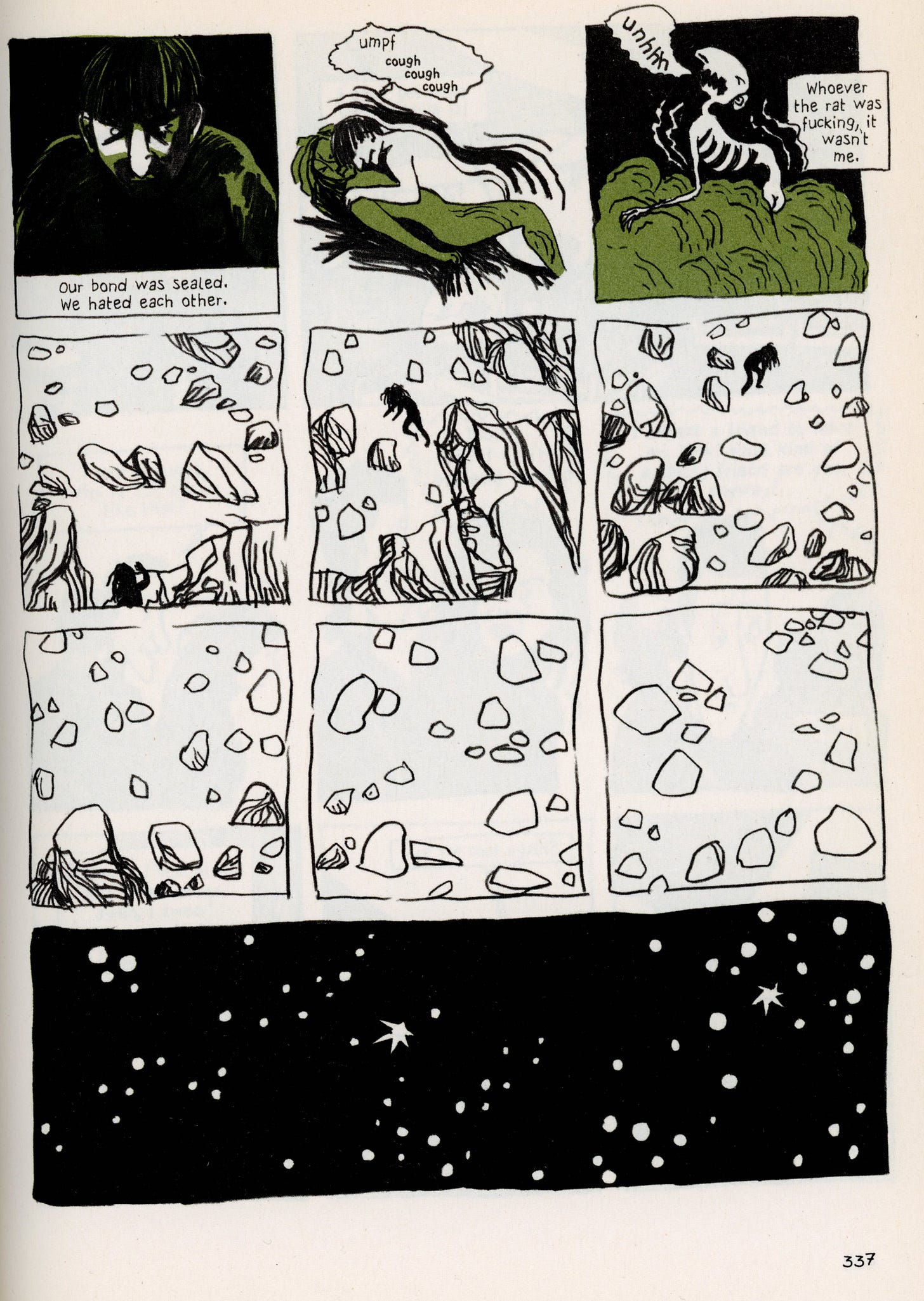

Ulli Lust discloses the raw and real of life on the road, in her intense graphic memoir, Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life. Like Davis, Lust travels unconventionally, illegally crossing borders, sleeping in abandoned buildings, and finding food wherever she can get it. Lust’s story centers the experience of traveling in Italy as a young, sexually desirable woman in a culture where men make the rules. The typical “romance” associated with Italy is thrown on its head by Lust’s dynamic, dark, fluid illustrations which depict encounter after encounter with terrible men.

Lust’s memoir does not inspire travel; instead, it opens a window to an ugly view–one just as real as any romantic take of Italy. In this way, Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life functions as an anti-travel memoir; it warns readers as opposed to beckoning them. The dark and realistic renderings are more compelling than any shiny picture of an Italian ruin in the countryside.

Lust accomplishes this insatiable pull to read through her craft, which is apparent in all elements of the book. Her art is fluid and smeared, intense and evocative. Panels depict dark scenes–both in action and color palette. Lust writes as an older woman looking back, but this passage of time is not reflected in the text–Lust mostly stays in the moment, no matter how terrible or ecstatic. She ably captures the real excitement and freedom felt by her teenage self, which is aided through snippets of letters and diaries she wrote at the time.

How does a young female encounter a new landscape? Ulli does so with gusto, yet also with growing fear and mistrust as she winds her way through the byzantine Italian streets. As a reader, we are immediately on edge from the moment she meets her traveling companion, Edi, in Vienna. Here, they try to make money for the trip by working at a local brothel – a first for both. It is prescient of what is to come–the currency of their bodies being requested over and over again as they travel south. This framing serves to remind the reader that it is not just Italy which holds the menacing presence of male attention–it is everywhere. Old and new life are shaped by negative masculine forces; we see in the book that they are simply, inescapably embedded in Western society.

However, Ulli strives to challenge and subvert norms–and as a self-styled punk-anarchist, she naturally is. In Italy, she also eschews traditional roles meant for women, but, she finds that the overtly patriarchal rules of Italy’s strict gender roles too hard to navigate without some “traditional” armor. In other words, she needs a male companion to preserve any sense of safety, and she tries to find one in a number of male travelers. But, in they end, they all want the same thing: sex.

There is an interesting, and heartbreaking, intersection of freedom and constraint in Lust’s account–Ulli so wants to be free, and in so many ways is, via her mode of travel, her ability to choose when she will get up, and how she will spend her days, yet time and time again she comes up against the male desire for her free body, which ultimately cages her.

Conclusion

As we’ve seen, travel often tests our limits and as such we expect tales of travel to focus on transformation, but these stories prove to be different than what “travel writing” calls to mind. For one thing, they are often more about the person writing than the place. The location can become a background rather than the catalyst for change.

Of course, to travel is to awaken our senses, and comics present an ideal mode through which to depict these sensations, from novel sights to enticing food to joint pain. Freely drawn and “unedited” in appearance or neatly ordered in panels, the formal considerations of comics affect the reader’s interpretation of the narrative distance in retelling these stories. Each creator’s individual style–from the more cartoon-y to the abstract, the neat to the messy–reflects what they experience, and in turn the readers’ understanding of the location and the journey.

Other SWPACA presentations we’re excited about:

Amaris will also be presenting on “Creative Placemaking and Poetic Mapping”

Graphic Nonfiction in Scholarly Communications - Stewart Brower, University of Oklahoma Tulsa

At Home in the Museum: Mediating Comics - Catherine Labio, University of Colorado Boulder

Undocumented Comics Production Pedagogy: Using Duncan Tonatiuh to Explore Colonial Writing Prejudices - Robert Watkins, Idaho State University

Art Cars and Underserved Youth - Amanda Palmer, Artocade/Art Cartopia Museum

Engaging Audiences in Reality: How Rhetors Use Graffiti to Teach on the Street - Jillian Dobrin, Texas Woman's University

The Truth Is in the Chalk: How Literary Journalism Has Stayed Alive through Our Obsession with Death - Carl Knauf, University of Alabama

Misrepresentations of Native Americans in Media - Jeanette Dedios, UNM Student