An Interview with Miriam Katin

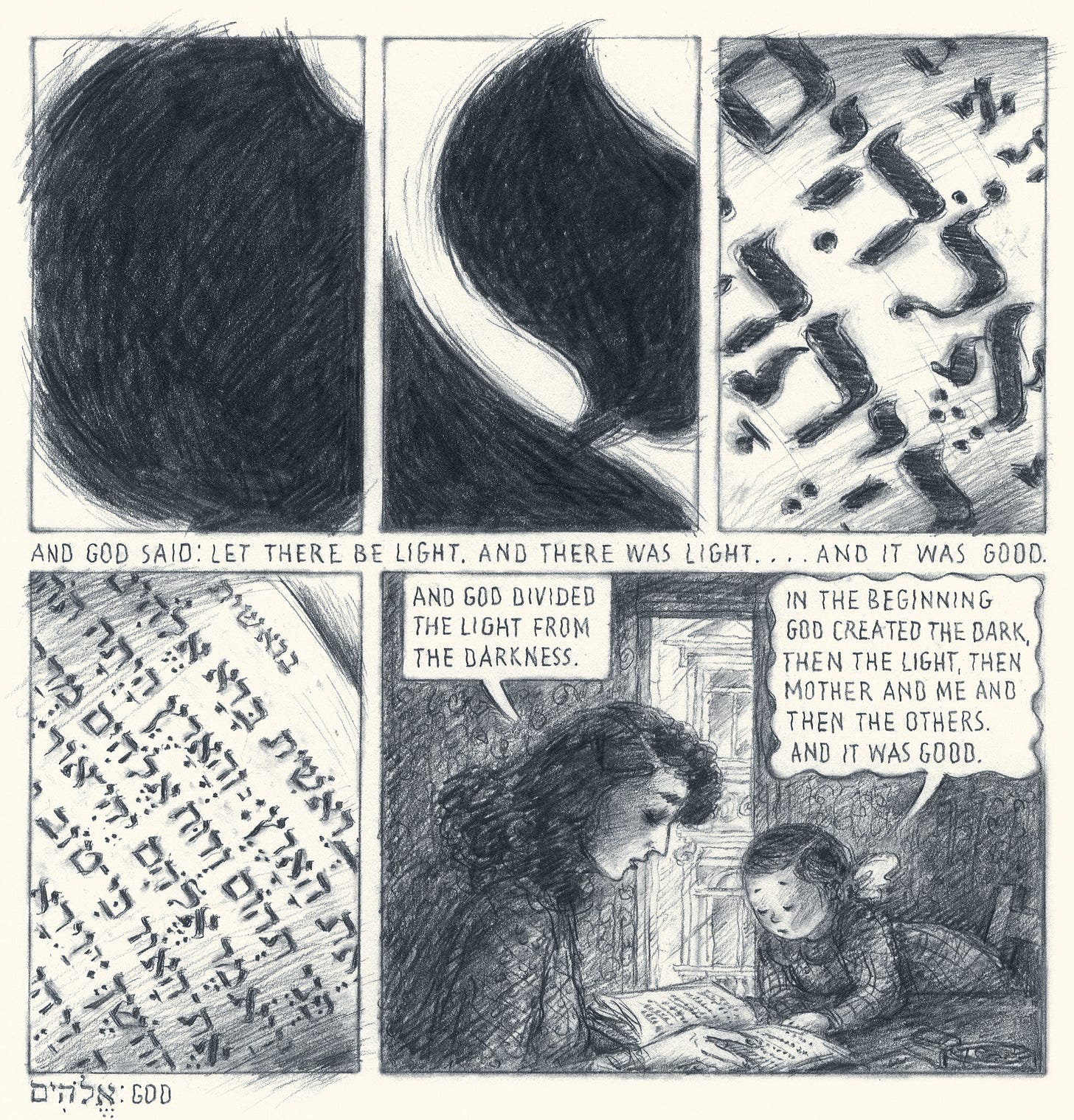

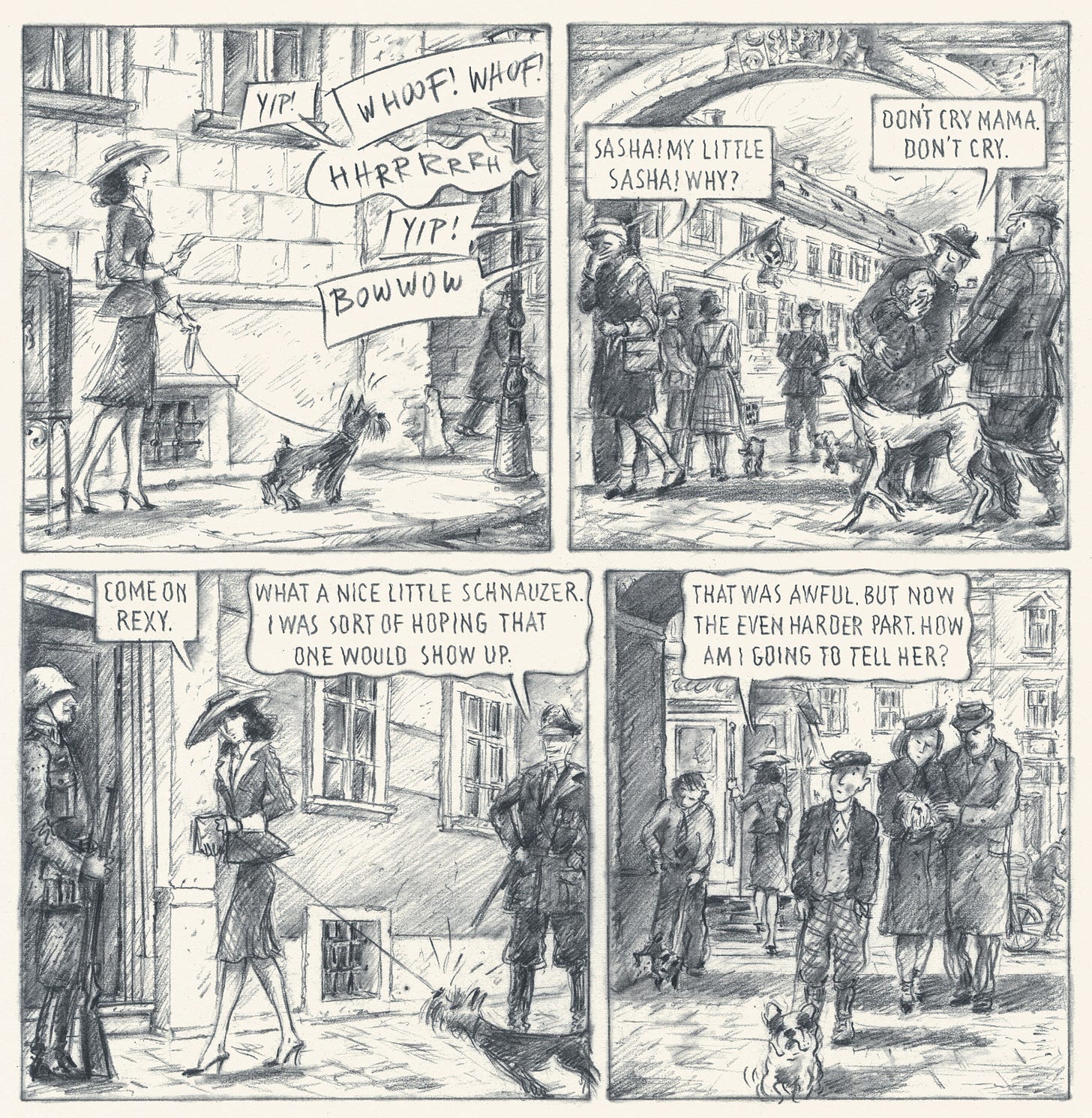

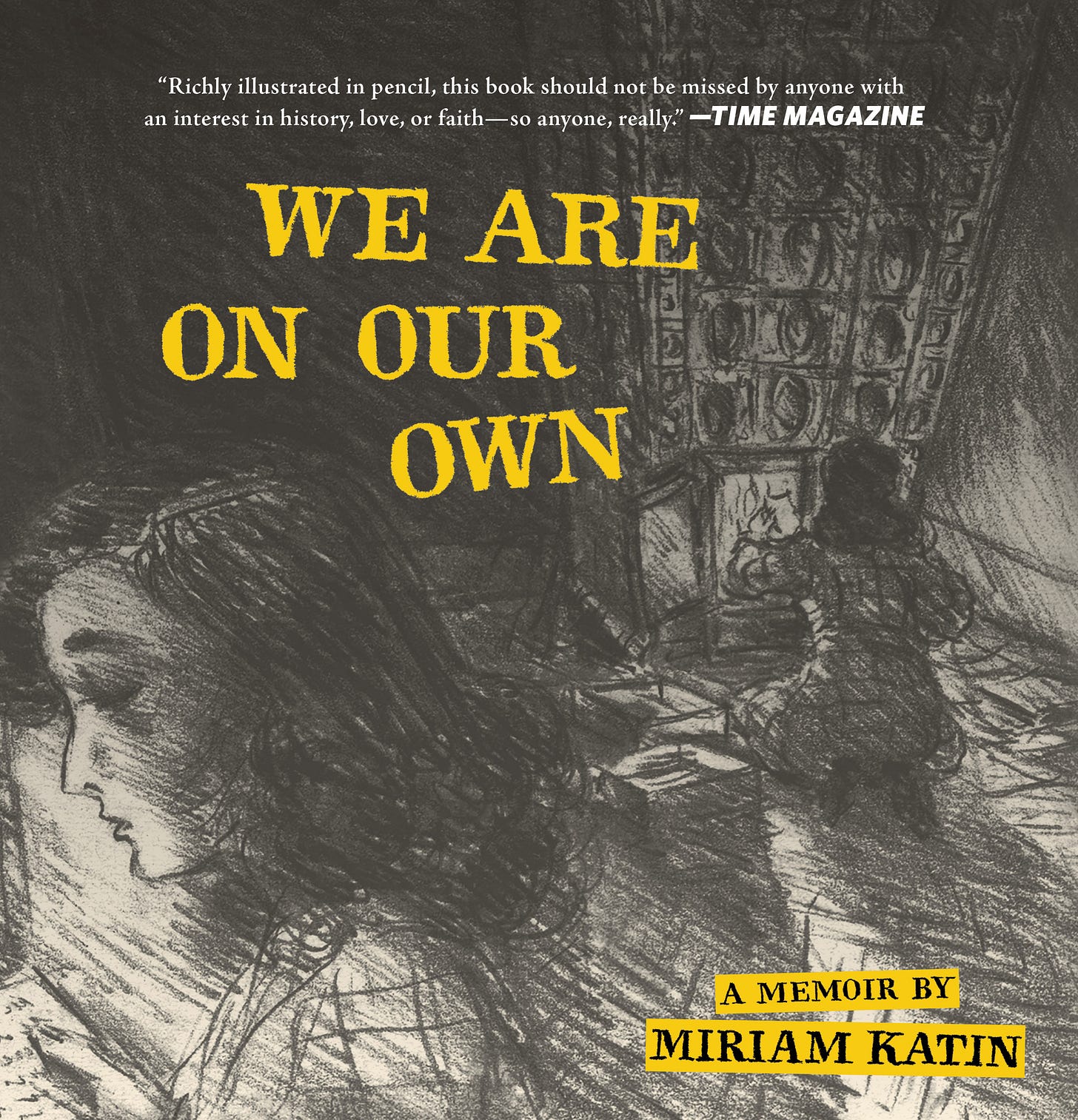

We Are On Our Own, the beautifully rendered WWII memoir by Miriam Katin, was re-issued this year by Drawn & Quarterly. Katin chronicles a childhood that was anything but ordinary, marred by the horrors of Nazi-occupied Hungary and a daring escape from Budapest, which she embarked on with her mother. Her pencil drawings capture the stark picture of wartime and sketch emotions intimately. We Are On Our Own is a testament to resilience, courage, and the enduring power of hope in the most dire of circumstances. We have written about the power of Katin’s work before and are delighted to have the opportunity to interview her.

Describe your comics journey—how did you get into making comics?

I was born in Hungary in 1942. Not a good time to be a Jew. My father was serving in the Hungarian Army, so he didn’t see me until age three. At the start of the rounding up the Jews, my mother purchased fake identification documents for us, “proving” she was a Christian servant girl from a village, with an illegitimate child.

With that, she left Budapest and wandered from place to place “hiding in plain sight.” After the war, we returned to Budapest and my father found us. How lucky we were. We lived in the city until the 1956 uprising against the Russians and then left for Israel, where my mother already had sisters living from after the war.

I had no formal education beyond ninth grade from Budapest, but I always loved advertisements and commercials, even back in Israel when I was 15 and had nothing to do. I had no money for education and I didn’t like the idea of becoming a hairdresser or cosmetician, which were the only choices. So, I walked into a commercial artists studio in Tel Aviv, not realizing it was one of a most prominent ones. I just looked at advertisements in the papers and saw one I liked and the signature SHAMIR was there. I found it in the phone book. So I was lucky, they took me in. I made a lot of tea, delivered and picked up things but also learned a lot.

At 18, entering the IDF (Israel Defense League) service, I kept telling them that I was a commercial artist. It so happened that they had a studio where they did what the army needed. There I did two more years of lots of learning, as not only were there some soldiers who graduated from Bezalel (the foremost art school in Israel), but also many artists came in to serve their annual civil service duty. Also, I was drawing from life all my life.

After the service, most people want to get out into the world and so I came to New York where I had an aunt. I met Geoff on the passenger ship on the way. Just my luck (again) that his father worked for a hosiery company and their New York office needed a commercial artist for package design.

How did you develop your unique comics style?

I just looked at a lot of art and “learned” from it. Then, when I was in the kibbutz (Ein Gedi by the Dead Sea 1981-1990) someone hoped to create an animation studio. They gave him a chance and we did work for Israeli Sesame Street and other programs, but there was no profit and the kibbutz does’t carry anything that doesn’t bring income. So the man left and I was compelled to do menial jobs until we returned to New York. To my great luck, New York was starting some studios. MTV, Nickelodeon, Disney, all had studios. It was five glorious years, but then it was all over.

Meanwhile I started to do small cartoons and comics and my colleagues encouraged me to do it seriously. So I found out about Drawn & Quarterly and sent them a sample. Well, Chris Oliveros actually called me and that’s how my work started with them.

P.S. I almost forgot, my boys were totally involved with Tin Tin. We had a great collection and actually that was my "bible." Whenever I needed any position or room or landscape, I always found help in them.

What are some of the joys and challenges of working on graphic memoirs?

It is very personal for me. I don’t invent stories. That makes it also limited, unless I’m being hired for something. But also, hopefully you get to work in a studio and then there is the challenge and joy of working with others. I worked on shows like Doug, Daria, and many things for Disney in New York.

In the years since the original release of We Are On Our Own, how have the conversations around the Holocaust and the experiences of Jewish survivors evolved, and do you think this new edition will resonate differently with readers today given the current climate of book banning and censorship?

When I started working with the subject, I was afraid to become “the Holocaust Lady” going from synagogues to Jewish Centers, but finally I had to take responsibility for what I created. And also to realize that there are fewer and fewer “real” survivors around. First I rejected to be called a survivor because I believed that only the people who were in the camps could be called that. I don’t know what to think of book banning but there always were books that shouldn’t have been published.

To see more of Miriam Katin’s work, visit her website.

I was looking at past interviews and really enjoyed reading this one with M kattin