An Interview with Jeff Horwat

"I liked the challenge of telling a complex story suggestively with images alone."

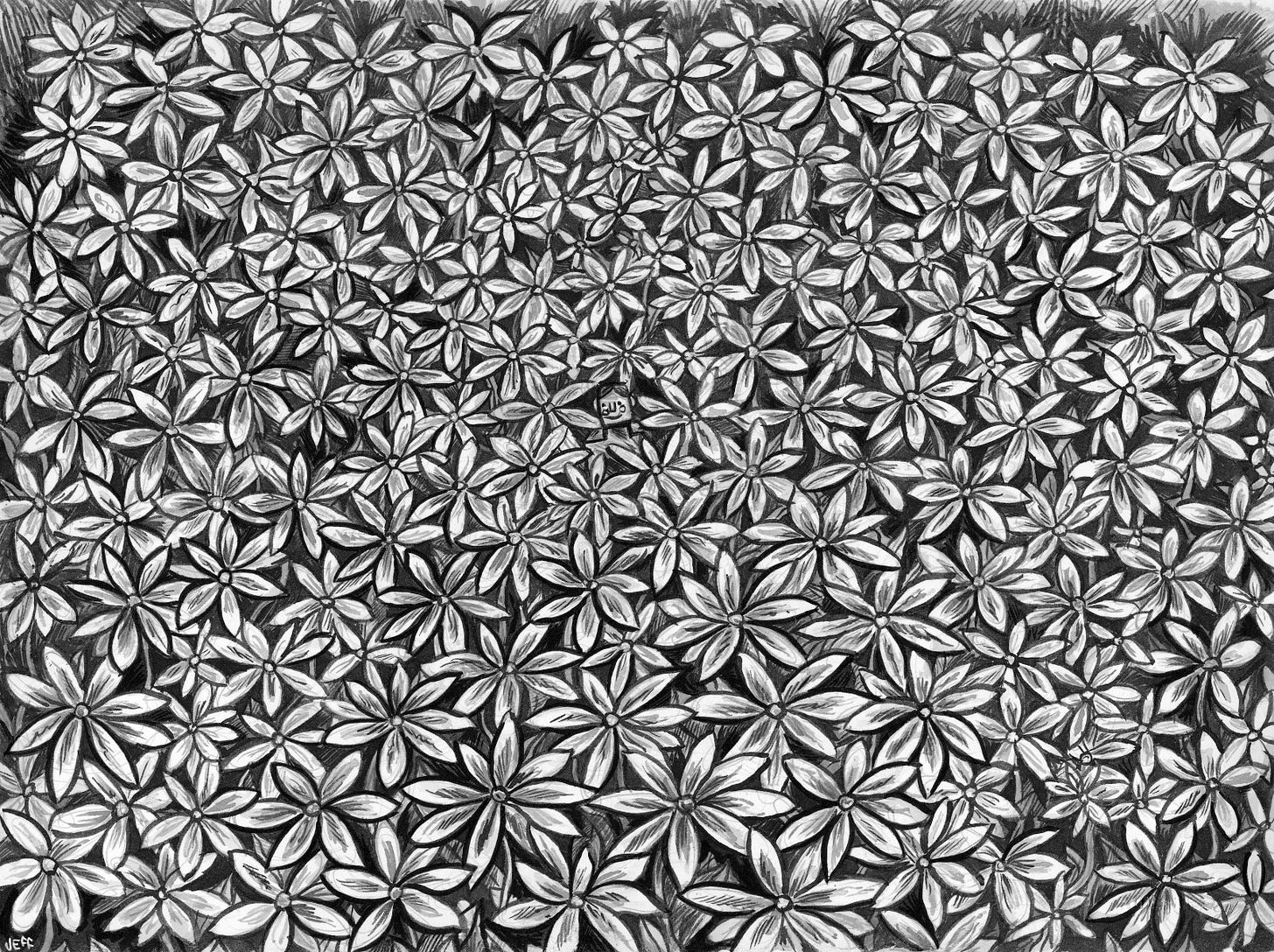

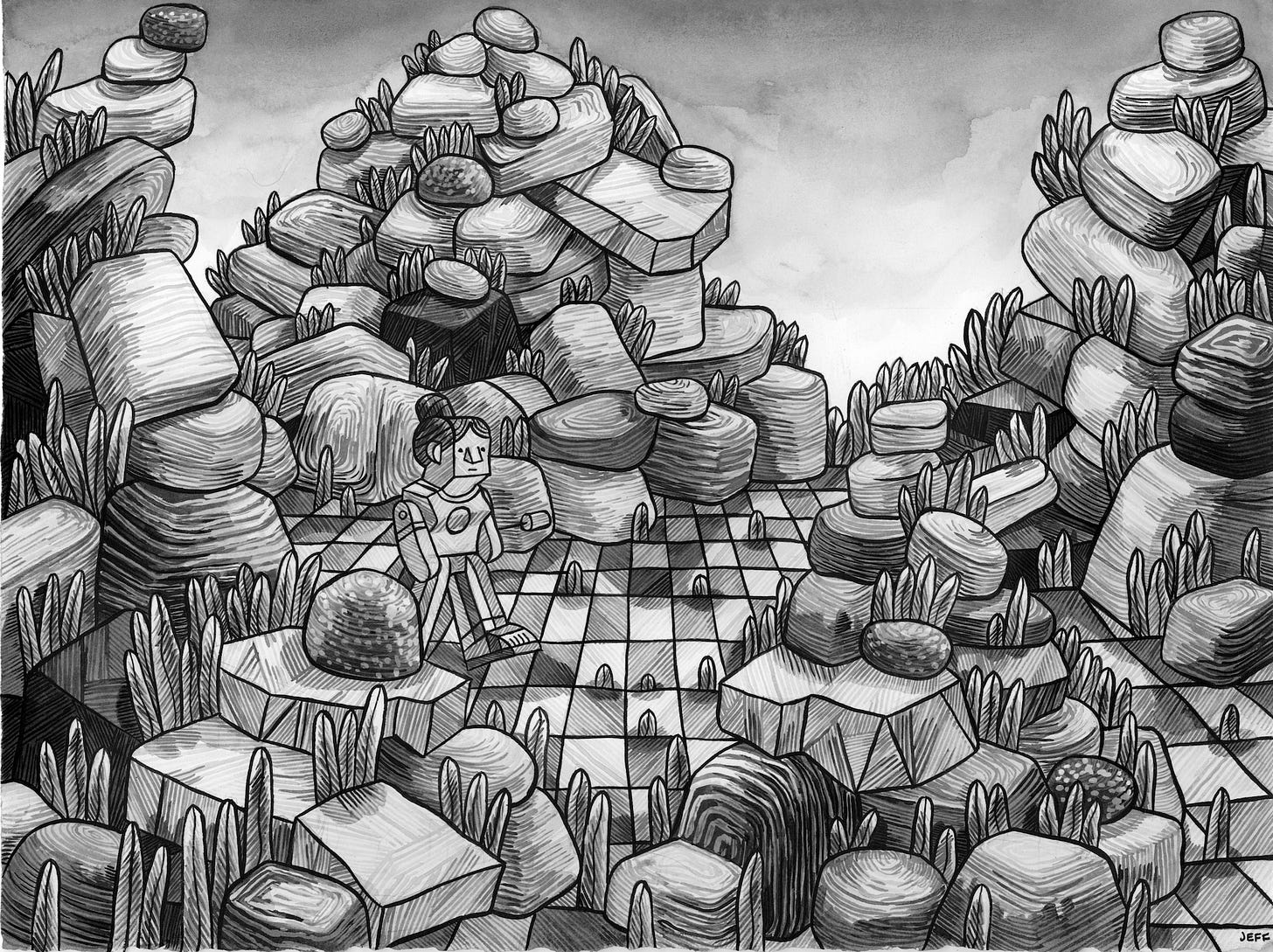

I met Jeff Horwat shortly after he moved to Albuquerque and began teaching in the art education department at the University of New Mexico. This summer, I was excited to dive into his complex and enchanting graphic novel, Nothing is a Cure. As his publisher describes, Nothing is a Cure takes readers on a journey through a surreal world, filled with symbolic objects and creatures that speak to existential emptiness and recovery. A wordless black-and-white graphic novel, it was informed by Buddhist meditation techniques and Jacques Lacan's psychological insights, offering readers a unique lens into the artist's psyche.

Side note: if you are in New Mexico, come say hi to Jeff & me at the Albuquerque Comics Show on September 23, from 10-5ish at 6600 Zuni Rd SE.

Describe your comics journey—how did you get into making comics?

I’ve always been an avid reader of graphic novels. I gravitated towards biographical memoirs like Art Speigelman’s Maus, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and David B’s Epileptic. While I revered graphic novels, as artist, I was more interested in creating narrative paintings than conventional comics. I never considered making my own graphic novel until about ten years ago when I exhibited a series of illustrative watercolor paintings for a solo show in an art gallery. Seeing the paintings on the walls, I began to see a coherent chronological narrative emerge.

Following the show, I felt compelled to create additional images that could fill in the narrative gaps between paintings to tell a more complex story than the original series alluded to. This realization led me to (re)create the watercolor paintings as ink wash drawings—a quicker way to tell the story while still referencing the aesthetic of the original watercolor paintings. Originally, I had thought to accompany each image with a poem I was amateurishly writing—initially seeing the narrative as more of a children’s book for adults than a conventional graphic novel. However, as I created new images for the narrative, I soon realized the illustrations were strong enough on their own. Furthermore, I liked the challenge of telling a complex story suggestively with images alone.

I casually worked on the experimental narrative project for another year, not knowing what I was doing or how it fit in the schema of current comic genres, but nonetheless I enjoyed the organic process I was engaged in. After about two years of infrequently working on the emerging narrative, I came across a copy of David Barona’s anthology about wordless novels and learned about Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, and Otto Knuckle. Their work resonated with me for its striking imagery, political message, and its ability to remain true to the image as the single driver of the narrative. I soon found other contemporary artists that created wordless novels like Eric Drooker, Shawn Tan, and Marnie Galloway. These artists both inspired me and also validated the wordless narratives I was interested in producing.

How did you develop your comics voice?

Coming to comics inadvertently through painting and illustration, much of what influenced my style were other illustrators like Edward Gorey, Tim Burton, and Dr. Seuss as well as the Surrealists—Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, Rene Magritte, Kay Sage, and contemporary ‘pop surrealists’ like Mark Ryden, Gary Basemen, Todd Schorr, and Tim Biskup. I’ve always been attracted to imagery that appeared playful, imaginative, and seemingly innocent, but was unassumingly philosophical and existential. As an artist, I’ve been exploring that tension between the naive and the existential—a surreal liminal space where I believe personal truths and understandings are formed. The wind-up toy imagery that I use in my paintings and current wordless narrative projects first emerged in art school as I was developing my own style. I had a collection of old toys from my childhood in my dorm room and I would often sketch them as observational drawing warm-ups. Sometimes I created little scenes with the characters that hinted at some kind narrative. These informal sketches and warm-up exercises informed the paintings I was creating and became the foundation of a visual language I would continue to develop for the next twenty years. These wind-up toy forms have continued to be a playful and surreal way to explore different psychological or philosophical ideas.

What are some of the joys and challenges of using real life experiences in your comics work?

My visual narratives draw heavily from autoethnography. I often refer to my own personal experiences to inform the creation of visual narratives as a way understand something I’m struggling but also in a way that speaks to broader contexts and is relatable to others. While rewarding and personally enlightening, a consequence of this kind of work is that it involves a lot of self-introspection and vulnerability. Because a lot of what inspires my work starts are personal problems or frustrations, I often spend time with difficult thoughts or memories to create the imagery as a way to understand those feelings. While this can be really therapeutic and often produces moments of profound self-understanding, it can also be emotionally exhausting. I’ve learned to be more careful with myself when working with my life experiences. My current work is more about experienced socials tensions than specific biographical details. The conceptual distance that allegories and complex metaphors provides has been a great way to explore sensitive personal content while also maintaining some degree of anonymity or control over the narrative itself.

Are you working on something now?

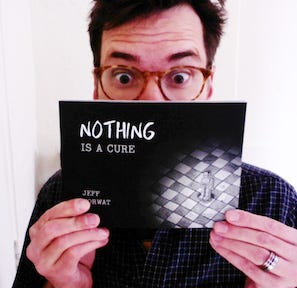

I published my first wordless book, Nothing is a Cure, in April. The book is available on Amazon and through Wolfson Press, the publisher’s website. This was a huge personal accomplishment as I’d been casually working on the book over the course of six years. Since, I’ve been publishing some scholarly writing based on Nothing is a Cure. Recently, I will have an article I wrote with two other scholars published in the Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies on comics, affect, and trauma where I discuss Nothing is a Cure through the Affect Theory.

I have a short wordless comic called ‘Good Mourning’ about grief, isolation, and the power of collective art-making that will be published this fall as part of an article I wrote for an upcoming issue of the Journal of Social Theory in Art Education. I am currently working on my second book titled “Living with the Living.” It is a wordless dystopian social commentary about schooling and education’s problematic relationship with creativity and anomalous learning. I’m hoping to have a completed draft of the narrative by the end of 2024.

You can learn more about these projects on my website: www.jeffhorwat.com. You can also follow me on Instagram, @jeffhorwat, where I post most recent pictures of my work, as well as family photos of my daughters and pictures from hikes I’ve done throughout the southwest.

Jeff Horwat PhD. is an artist, teacher, and scholar from eastern Pennsylvania. His creative scholarship explores the intersections of wordless novels, arts-based research, and psychoanalytic theory. He is the author of Nothing is a Cure, and has published scholarship in Visual Arts Research, Art Research International, Artizein: Arts & Teaching Journal, and the Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies. He lives in Albuquerque with his wife and two daughters, where he teaches in the art education department at the University of New Mexico.

This is a great interview and the book is awesome!