An Interview with Andy Warner

Andy Warner has been drawing ever since I knew him back in college. It’s been a joy to see his comics output and craft grow over the years; I still get a thrill anytime I come across his funny, informative, poignant books in the library or bookstore. Sometimes journalistic, sometimes personal, Andy’s comics are always memorable. We are happy to feature his thoughts on comics this week. — Nora

Describe your comics journey--how did you get into making comics?

I was exposed to comics in a positive way from early childhood, thanks to my parents. My dad always loved the newspaper comics page, and we read it together growing up. My mom taught us French using bande dessinées (BDs) like Tintin, Marsupilami and Lucky Luke. From a really young age, I was always drawing comics of my own. My parents have some amazingly old stuff of mine in their attic, and I've even got a little "about myself" book from first grade where I wrote about wanting to be a cartoonist or a mime. I went with cartoonist, but it took a while to get there. I convinced myself in middle or high school that a career in the arts was out of reach, and I focused on academia. I did my undergrad in Near Eastern Studies and Comparative Literature, and expected that would be the path I continued on. I never stopped drawing or reading comics, though. They were always a huge part of my life.

While I was working on my thesis in college, I realized comics were the thing that really fascinated me, and held my attention in a way that nothing else did. So I switched tracks. I'd put together a small comics publication in college and after graduating, I moved out to San Francisco to intern at McSweeney's and work as a graphic designer on a magazine while I taught myself how to do small press publishing and figure out indie comic conventions.

After a few years, the economy imploded, I lost most of my graphic design clients, and decided to go to grad school to get an MFA in comics from the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont. I had a great time there, and found a community that remains a bedrock of my career. It was also where I figured out that nonfiction comics were what I was good at. My last year there, I co-founded an anthology called Irene with two other CCS students, Dakota McFadzean and dw, in which we published a bunch of our own work and were lucky enough to be in the right place to publish early comics that cool people around us like Ben Passmore, Tillie Walden and Casey Nowack were making.

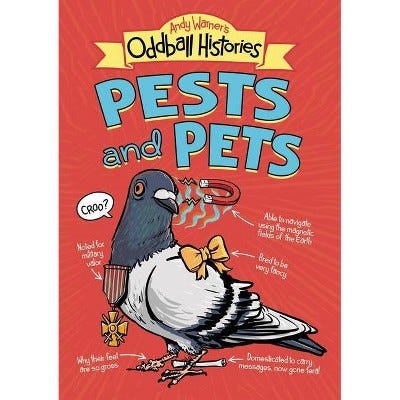

After graduating, I made money doing freelance comics journalism, comics advocacy, and illustration work for a bunch of different places, outlets and people. One of those was the Nib, where I started getting commissioned more and more until they eventually hired me on as a contributing editor in 2016. The rise and fall and rise and fall of the Nib is its own narrative that's too long to get into here, but I'm still working for them on their print magazine, which comes out 2-4 times a year, pandemic depending. Meanwhile, a minicomic I'd made in 2012, collecting the short run of my one and only webcomic attempt found its way into the hands of a book editor in New York. She reached out to see if I wanted to make it into a book, which I very much did. That book, Brief Histories of Everyday Objects, came out in 2016. Since then, I've published three other books: This Land is My Land (with Sofie Louise Dam), Spring Rain, and Pests and Pets. They range from druggy memoirs about unsolvable political violence to jokey YA nonfiction histories.

How did you develop your voice/unique comics style? A lot of your comics we have read are research-driven: how do you decide what to write about?

An editor of mine once described my reporting beat as "stoned on wikipedia," which struck me as good a description of my work as any other. I have a strange career since (almost) everything I do is nonfiction, but I work in a lot of different spaces—from YA to advocacy to journalism to memoir. They’re all nonfiction, but they all have different sets of rules. You don't treat a silly history of a toothbrush the same as a serious explainer about political violence. From the early days of my career, I was working on serious stuff at the same time as fun stuff. It’s like nonfiction code switching: you think about your audience, you think about how they would react, and then you tailor your voice and work for that. That doesn’t mean censoring yourself; you just put yourself in the shoes of the person reading it: This person has picked up this thing to read because you’ve managed to interest them, and it’s fine to challenge them—you should challenge them—but challenge them on terms that they understand and can accept.

You can write very complex stuff for kids, but you can’t write for kids like you write for adults and vice versa. You also can’t write for screens like you write for print. In terms of how I decide what to write about, the fun thing about nonfiction is that you don't have to make stuff up–the world is really fascinating. It's pretty easy to find stuff to be interested in, and the trick is then finding a way to convey that interest to the reader, and take them along with you as you dig into a topic.

How do you think the comics form creates a community forum?

Since at least the 1970s in North America and the rise of the underground, comics have always been very heavily about the community. The very well established comics convention circuit in the US and Canada creates a venue where peers are able to meet up, kind of like for writers conferences, but they're actually selling their new material to a live audience to fund their plane ticket and accommodations, kind of like playing a music show. It's cool, kind of unique to the medium, and fosters a strong sense of fellowship, connection and exchange inside of the community of creators. And that's just the North American perspective. Globally, comics are part of a transnational "nerd" culture that's only grown and become more knit together, first with the internet, and then social media.

There are people all over the world who love comics and read them. There are different traditions of comics, and comics fandoms exist everywhere. Wherever you go, you can find communities of people expressing themselves through comics. That was actually an experience I had growing up and moving around as a kid, reading French comics, reading Spanish comics, reading Japanese comics. This happened again in my adulthood, through my involvement, starting in 2007, with Samandal, a Lebanese comics anthology that was published in three different languages — Arabic, French and English — and featured artists from all over the world. So from early on in my career, through publishing work and being friends with the Samandal community, I had access to a broad international community of cartoonists. This was expressed in what we were later able to do with Irene. The last issue that we put out before it imploded had a cartoonist from every continent, including Antarctica! And this also carries over to my work with the Nib, which has always had an editorial mandate to publish as many non-American cartoonists as we could for our (mostly) American readership.

Are you working on something now?

Yeah! I just had a YA book about animal domestication come out in September called Pests & Pets. I'm currently working on the follow up, which is about people, plants and imperialism (for kids!). I'm in the inks for it now, which is always the most exhilarating part. I'm also slowly working on a book of adult-oriented journalism about the communities living along the volcano coast of the big island of Hawaii but I can't talk too much about it yet. And you can check out my first three books at my website, http://andywarnercomics.com/books.